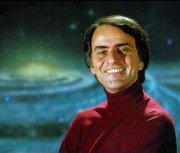

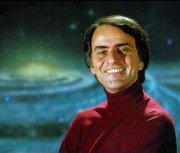

Yesterday I blogged about my 11th-grade math teacher, Mr. Arrigo, one of my greatest teachers ever. But any list of my greatest teachers must include Carl Sagan, even though he wasn’t “my” teacher any more than he was everyone else’s in the whole world.

Sagan’s famous Tonight Show appearances happened right around the time I was old enough to stay up and see them. Early on I remember being annoyed by his criticisms of Star Wars (to wit: that spaceships don’t make whooshing noises in space, that Chewbacca deserved a medal at the end too, etc). But then my mom, who I think had a bit of a crush on him, urged me to read Broca’s Brain, and I was hooked on his brand of science education.

Sagan’s famous Tonight Show appearances happened right around the time I was old enough to stay up and see them. Early on I remember being annoyed by his criticisms of Star Wars (to wit: that spaceships don’t make whooshing noises in space, that Chewbacca deserved a medal at the end too, etc). But then my mom, who I think had a bit of a crush on him, urged me to read Broca’s Brain, and I was hooked on his brand of science education.

Then came Cosmos, which was eagerly anticipated in our household. We counted down to its premiere for weeks. When it finally aired, the cheesy new-age music and Sagan’s, er, limited acting abilities — the camera lingered forever on what was supposed to be his awestruck face as he sailed through the universe in his kinda lame “ship of the imagination” — left us at first unenthused. But then came his story of Eratosthenes and I got another one of those emotional learning moments that I wrote about yesterday. The following is from Cosmos, the companion book to the PBS series:

[Eratosthenes] was the director of the great library of Alexandria, where one day he read in a papyrus book that in the southern frontier outpost of Syene, near the first cataract of the Nile, at noon on June 21 vertical sticks cast no shadows. On the summer solstice, the longest day of the year, as the hours crept toward midday, the shadows of temple columns grew shorter. At noon, they were gone. A reflection of the Sun could be seen in the water at the bottom of a deep well. The Sun was directly overhead. […]

Eratosthenes asked himself how, at the same moment, a stick in Syene could cast no shadow and a stick in Alexandria, far to the north, could cast a pronounced shadow. […]

The only possible answer, he saw, was that the surface of the Earth is curved. Not only that: the greater the curvature, the greater the difference in shadow lengths. […] For the observed difference in the shadow lengths, the distance between Alexandria and Syene had to be about seven degrees along the circumference of the Earth [which] is something like one-fiftieth of three hundred and sixty degrees, the full circumference of the Earth. Eratosthenes knew that the distance between Alexandria and Syene was approximately 800 kilometers, because he hired a man to pace it out. Eight hundred kilometers times 50 is 40,000 kilometers: so that must be the circumference of the Earth.

This is the right answer. Eratosthenes’ only tools were sticks, eyes, feet, and brains, plus a taste for experiment. With them he deduced the circumference of the Earth with an error of only a few percent […] He was the first person accurately to measure the size of a planet.

In the TV show, when Sagan said matter-of-factly, “This is the right answer,” I got a lump in my throat. At once I was propelled farther down the paths of learning, teaching, science, and, of course, Carl Sagan fanhood.

It is more than just a shame that Sagan died before his time of a rare disease, ten years ago today. (This blog post is participating in a Carl Sagan “blog-a-thon” to commemorate the occasion.) There is no doubt that if he were alive today, he would never have permitted science to be debased by politics to the extent that it has in recent years. Sagan knew that we ignore science at our peril and excelled at conveying that message. He saved the world once before, by popularizing the nuclear winter theory of the aftermath of even small nuclear wars, assuring those insane enough to consider such wars that they could never avoid spelling their own doom as well as their enemy’s. Who will take up his mantle and bring the Promethean fire of science back to light a world darkened by his absence?

Let’s get this out of the way right now: The Godfather was a supernaturally good movie. The story, the characters, the performances, the settings, the cinematography, the editing, the music

Let’s get this out of the way right now: The Godfather was a supernaturally good movie. The story, the characters, the performances, the settings, the cinematography, the editing, the music Part II? Lots of that was great, too. Numerous memorable moments. “I know it was you, Fredo. You broke my heart. You broke my heart!” De Niro as the young Vito — incredible. But does it add up to much more than the sum of its parts like the original? No. Most of its flaws are with the plot, which is at times confusing and inconsistent. For instance, I have never been able to find anyone able to answer these questions (warning: spoilers follow):

Part II? Lots of that was great, too. Numerous memorable moments. “I know it was you, Fredo. You broke my heart. You broke my heart!” De Niro as the young Vito — incredible. But does it add up to much more than the sum of its parts like the original? No. Most of its flaws are with the plot, which is at times confusing and inconsistent. For instance, I have never been able to find anyone able to answer these questions (warning: spoilers follow): Sagan’s famous Tonight Show appearances happened right around the time I was old enough to stay up and see them. Early on I remember being annoyed by his criticisms of Star Wars (to wit: that spaceships don’t make whooshing noises in space, that Chewbacca deserved a medal at the end too, etc). But then my mom, who I think had a bit of a crush on him, urged me to read

Sagan’s famous Tonight Show appearances happened right around the time I was old enough to stay up and see them. Early on I remember being annoyed by his criticisms of Star Wars (to wit: that spaceships don’t make whooshing noises in space, that Chewbacca deserved a medal at the end too, etc). But then my mom, who I think had a bit of a crush on him, urged me to read

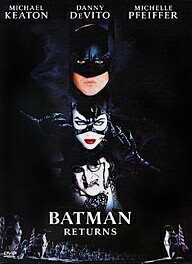

This made me think of 1992’s Batman Returns. What “returns” in that movie? Nothing; Batman hasn’t been away since the events in 1989’s Batman. On the contrary, in that title, “Returns” refers to the fact that it’s been three years for the audience since the last Batman movie. Batman “returns” to moviegoers. (Or perhaps, more cynically, Batman provides “returns” on the studio’s investment. Hard to be too cynical about the studio [Warner Brothers] and the franchise that famously required director Joel Schumacher to make Batman & Robin “more

This made me think of 1992’s Batman Returns. What “returns” in that movie? Nothing; Batman hasn’t been away since the events in 1989’s Batman. On the contrary, in that title, “Returns” refers to the fact that it’s been three years for the audience since the last Batman movie. Batman “returns” to moviegoers. (Or perhaps, more cynically, Batman provides “returns” on the studio’s investment. Hard to be too cynical about the studio [Warner Brothers] and the franchise that famously required director Joel Schumacher to make Batman & Robin “more