Webmaster deletes leaf node, then performs some site maintenance.

CHUD!

[This post is participating in M.A. Peel’s Comedy Blog-a-thon.]

It may be immodest of me to identify, as my “purest comedic moment,” one that I helped to create. But when I try to think of one that I merely experienced, there are a thousand different ones vying for the top spot. On the other hand, of my own comedy there was a single moment that stands above the rest.

As I mentioned a few months ago, some friends and I won our ninth grade talent show with a comic act called “The Epiphany County Choir.” Wearing plaid flannel shirts, bad haircuts, and dumbfounded expressions, we pretended to be country bumpkins from Nebraska newly arrived in the Big Apple. We sang “When it’s hog-calling time in Nebraska” to much laughter and applause.

A short time later, through some connections of Chuck’s as I recall, we got a gig performing our Epiphany County Choir act in front of a studio audience on a local cable-access show. We arrived at the studio early on a Saturday morning excited and nervous, chatted a bit with the station manager, and then were shown onto the stage in front of our audience: a class of 2nd-graders from Harlem.

The show must go on. We gamely performed “Hog Calling Time” in character, but to say our humor was lost on them is giving too much credit to the connotative powers of the word “lost.” We left the stage and huddled in the waiting room with the station manager and the schoolteacher, who registered her displeasure at the choice of entertainment for her charges. She wanted to know if we had anything more age-appropriate to perform for her kids.  Chuck, apparently interpreting this to mean “race-appropriate,” indelicately suggested, “We do know the theme song from The Jeffersons.”

Chuck, apparently interpreting this to mean “race-appropriate,” indelicately suggested, “We do know the theme song from The Jeffersons.”

Because the world is funny, today Chuck is a professional diplomat.

Embarrassing at the time, that episode is funny in hindsight, and Chuck has gotten his share of ribbing for his gaffe, but that wasn’t my purest comedic moment. Read on.

We reprised our Epiphany County Choir act the following year to reasonable acclaim, with about twenty minutes of new material. The year after that we decided to stage our own hour-long show: “The Epiphany County Choir Home-For-Christmas Television Special” (in April).

Feeling we hadn’t sufficiently promoted the show in advance, we stood outside the entrance to our school on show day, lined up in our flannel shirts and in character, repeating the following in unison over and over and over for about forty-five minutes as students arrived for classes: “Come to the Epiphany County Choir Home-For-Christmas Television Special, 11:30 in the auditorium for free! Come to the Epiphany County Choir Home-For-Christmas Television Special, 11:30 in the auditorium for free! Come to the Epiphany County Choir Home-For-Christmas Television Special, 11:30 in the auditorium for free!” You try it, see how long you can keep it up.

The show included a performance of “Silver Bells” on a set of handbells; an Andy-Kaufman-style pantomime to a recording of “So Long, Farewell” from The Sound of Music; an a capella rendition of the theme music from The Odd Couple; an audience “sing-along” consisting of nothing but hand-clapping; and more. We were a hit; the crowd loved us.

But the coup de grace was the “Chud game.” Steve set the stage with a few minutes of (intentionally) bad stand-up about Chud, the neighboring county to Epiphany. “They call themselves Chuddites over there,” he told the audience with barely suppressed mirth, “but we just call ’em Chuds!” (Whereupon we in the Choir crack up.) There followed several supposedly disparaging Chud jokes — e.g., “How many Chuds does it take to screw in a light bulb? Fifteen!” — and then our helpers distributed Chud cards to the audience members.

The night before, we had drawn up hundreds of Chud cards by hand. These were Bingo cards, but with four columns apiece, labeled C, H, U, and D. Each card was different, just like real Bingo cards, but they were all rigged to win simultaneously when we called the four prearranged “Chud numbers.” I should mention that this was more than a year before “C.H.U.D.” stood for Cannibalistic, Humanoid Underground Dwellers.

After the Chud cards were distributed, Steve announced that the winner would receive a prize. The prize was beef jerky. A few days earlier, Andrew and I had gone to a snack-food wholesaler to buy enough beef jerky for the whole audience.

After the Chud cards were distributed, Steve announced that the winner would receive a prize. The prize was beef jerky. A few days earlier, Andrew and I had gone to a snack-food wholesaler to buy enough beef jerky for the whole audience.

I cranked the handle of a genuine Bingo cage we had secured from somewhere, and I handed the chosen numbers to Steve one at a time. Although he made a big show of trying to read the numbers off the balls, of course he didn’t actually; instead he announced the numbers we had arranged the night before. “C-8!” “U-32!” “D-49!” By the third number it was obvious to the audience what we were up to and they began laughing and clamoring. Steve threw an unrehearsed curveball, announcing a number we hadn’t planned, and I was momentarily furious with him, worried that someone might prematurely win the game — but no, he succeeded in building a little suspense.

When he finally announced, “H-18!” the entire audience jumped to its feet and roared, “CHUD!” in unison. Somewhere there is video footage of me, Steve, and the others in the Choir with perfectly astonished looks on our faces as the crowd dissolved into screaming laughter. (We never could have pulled it off without cracking up ourselves if we hadn’t stayed awake the entire night before, preparing the show and rehearsing, making ourselves weary and slightly sick from too much beef jerky.) In my wildest dreams I could not have imagined causing such merriment or producing such a response. It was my purest comedic moment.

Matchmaker, part 1

A few days ago I read an article speculating that the one-man computer-dating company, PlentyOfFish.com, may be worth a billion dollars.

A few days ago I read an article speculating that the one-man computer-dating company, PlentyOfFish.com, may be worth a billion dollars.

This inspired me to write the following rambling reminiscence of my forays into computer dating services — not as a customer, but as an operator.

It all started when I taught myself the computer language BASIC in anticipation of winning an Apple II computer in a magazine contest. To my great surprise I didn’t win (and in related news: I’m not the center of the universe) but, luckily for me and my nascent programming skills,  my new friend Chuck had a computer at home, which was almost unheard of in those days. (His dad was a professional programmer and weekend computer hobbyist.)

my new friend Chuck had a computer at home, which was almost unheard of in those days. (His dad was a professional programmer and weekend computer hobbyist.)

Chuck and I bonded over our shared nerdiness. How nerdy? In our seventh-grade music class, one homework assignment was to develop a board game illustrating the differences between different eras of classical music history. We undertook an electrical engineering project, drawing up circuit diagrams, buying parts at Radio Shack, and soldering them together in Chuck’s basement.  The resulting game, which we called ElectroMusiQuiz, required players to answer music-history questions on cards that could then be inserted into a slot that would cause the right answer to appear on a 7-segment LED. A right answer meant you could advance your gamepiece across the board. ElectroMusiQuiz was extremely crude, but on the day everyone brought in their board games, ours was the one everyone wanted to try!

The resulting game, which we called ElectroMusiQuiz, required players to answer music-history questions on cards that could then be inserted into a slot that would cause the right answer to appear on a 7-segment LED. A right answer meant you could advance your gamepiece across the board. ElectroMusiQuiz was extremely crude, but on the day everyone brought in their board games, ours was the one everyone wanted to try!  (This was before ubiquitous electronic goodies, you must understand, when upside-down illegible-word calculator games were all the rage.) It earned us a commendation from the principal’s office.

(This was before ubiquitous electronic goodies, you must understand, when upside-down illegible-word calculator games were all the rage.) It earned us a commendation from the principal’s office.

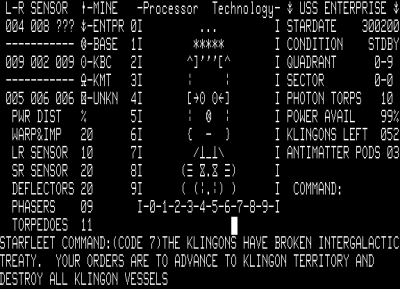

Over the next couple of years, Chuck and I spent countless afterschool hours with our heads together in front of his computer, laboriously typing in long program listings from issues of Byte and Dr. Dobbs Journal of Computer Calisthenics & Orthodontia, trying out our own creations in NorthStar BASIC and later UCSD Pascal, or just loading Adventure or Trek-80 from a 500-baud audio cassette and playing until dinnertime.

The state of the art in computer gaming circa 1980. We loved it.

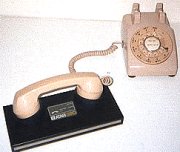

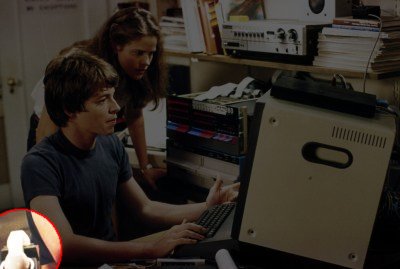

Occasionally we’d watch in awe as Chuck’s dad used a modem to connect his computer to the mainframe at his office. It was an acoustic modem, the kind Matthew Broderick uses in WarGames, where a telephone handset is jammed into a pair of rubber cups, one housing a mic for listening to the screechy data sounds from the handset, and one housing a speaker for making screechy data into the handset’s mic. Such a device was only possible, of course, at a time when telephone handsets were all a standard size and shape.

Occasionally we’d watch in awe as Chuck’s dad used a modem to connect his computer to the mainframe at his office. It was an acoustic modem, the kind Matthew Broderick uses in WarGames, where a telephone handset is jammed into a pair of rubber cups, one housing a mic for listening to the screechy data sounds from the handset, and one housing a speaker for making screechy data into the handset’s mic. Such a device was only possible, of course, at a time when telephone handsets were all a standard size and shape.

One day in eleventh grade (1982-83) we learned that our school had a computer terminal with a built-in acoustic modem — a teletype-style machine, with a roll of paper for printing the output, line by line, from whatever computer you connected it to. Around the same time we learned that it was almost time for our school’s annual Carnival, and we hatched this idea: we would operate a computer-dating booth. A few weeks before Carnival, we’d circulate personality questionnaires to all students. We’d collect them and enter the data from the completed forms into a computer-dating program that we would write for Chuck’s computer. On the day of Carnival, we would set up the terminal in an unused classroom, connect it by phone to Chuck’s computer at home, and direct it to output a list of the five best matches (as determined by our program) for anyone who showed up and handed over a couple of Carnival tickets.

To my modern self, the ambitiousness of that plan is breathtaking. As a harried parent who works full time (married to another harried parent also working full time), for whom merely writing in my blog requires stealing moments here and there for days on end, the level of effort that plan implies makes me cringe. But we were young and our responsibilities were few. Somehow in the space of a few short weeks we:

- Got approval from some teachers to set up this “booth” and use the teletype;

- Wrote a personality questionnaire (filled with random questions pulled out of thin air);

- Sweet-talked the Social Studies department’s office into letting us have some of their mimeograph stencils for typing up the questionnaire — most of which we ruined with imperfect typing (including one memorable copy in which the text was perfect but which was then cut in half by a line of underscores I added at the bottom for the submitter’s name!);

- Got high on mimeograph fumes and then distributed the blank questionnaires to over a thousand schoolmates;

- Wrote, debugged, and tested the software for enabling data entry, saving and loading the data to and from a disk file, and executing the matchmaking computation;

- Roped Chuck’s dad into staying home on the day of Carnival in order to assist with establishing the modem connection and any technical issues that might come up;

- Collected completed questionnaires from hundreds of students;

- Made a crooked deal with one classmate to ensure a certain student appeared in her list of matches (and vice versa) in exchange for an invitation to her upcoming sweet sixteen party.

On the night before Carnival there were still hundreds of questionnaires to enter into Chuck’s computer. There were four of us working at it: me and Chuck; my girlfriend Erica, and her friend Mari. It was slow, gruelling work that we did in two-person teams, one reading data aloud from the forms, the other typing it in, occasionally saying, “Wait, wait…” After a while, the reader’s voice would grow hoarse and the typist’s hands would cramp up, and they’d switch roles, or swap in the other two-person team.

As the hours dragged on long past midnight and our weariness came close to despair, there was one consolation for me at least: while Chuck and Mari worked and it was Erica’s turn and mine to rest, we made out almost continuously, like the indecent sixteen-year-olds we were.

Finally, some time past 3am, the last questionnaire was entered. We amused ourselves for a short time by querying the matching engine a few times to see which of our classmates matched up with whom (untroubled by the ethical or privacy compunctions — see “crooked deal” above — that would constrain our later adult selves), then called it a night.

Not enough sleep later, we went to school and set up the computer-dating room. We pushed all the chairs and desks in a classroom toward the back wall and wheeled in the teletype, then brought in a telephone with a cord long enough to reach the nearest extension jack across the hallway in the Foreign Languages office. Next we called Chuck’s dad at home and instructed him to begin the computer connection and then jammed the handset into the terminal’s modem. After fiddling around with various settings (learning on the fly about the difference between “full duplex” and “half duplex”), we were up and running! To our considerable surprise.

Almost as soon as we posted our sign on the classroom door, a line formed out the room and down the hallway. We began collecting Carnival tickets, running the matching engine, and delivering the results — a list of fellow students’ names — in the form of printouts torn off the teletype. But the matching engine was slow, taking up to five minutes to produce one set of results, and the line of “customers” just grew and grew. Now and then someone tripped over the phone line and disconnected us, and we’d have to call Chuck’s dad again and arrange a mutual jamming of telephone receivers into modems.

As the delays mounted, the crowd’s mood started to sour, and they began clamoring for faster service. To add to our troubles, the teletype began printing strings of random characters at unpredictable intervals, occasionally dropping the connection! Before long we figured out that this was caused by the noise of the crowd getting into the acoustic modem and being mistaken for data! So we moved the queue into the hallway, closed the door, and admitted just one person at a time.

A few hours later, we closed the computer-dating booth. We had collected a small mountain of Carnival tickets and congratulated ourselves on a job well done.

(To be continued…)

Starting again again again

I’m still not managing to melt the pounds away, so I’m resetting the start date of my weight-loss effort to today, but keeping the end date the same (July 1st). That gives me 212 days to lose 29 pounds; less than a pound a week. That should be doable, right?

I plan to reduce my portion sizes, pay closer attention to the nutrition-per-calorie content of what I eat, get on my bike more often, and use Kinetic as my simulated personal trainer.

Or maybe I’ll just hibernate for the winter and metabolize my fat reserves.

Don’t be so negative

This week’s Car Talk Puzzler is as follows:

In a certain family each daughter has the same number of brothers and sisters. Each son has twice as many sisters as brothers. How many sons and daughters are there in the family?

This is obviously a very straightforward problem in algebra. Let G be the number of girls in the family and B be the number of boys. Each girl has G-1 sisters and B brothers. Each boy has G sisters and B-1 brothers.

Converting the problem statement to a system of equations gives us:

G-1 = B

2G = B – 1

Now it’s a simple matter to rearrange the terms and solve for G or B. Let’s start by adding 1 to each side of the second equation:

2G + 1 = B

Now let’s substitute G – 1 for B, since the first equation tells us they’re equal:

2G + 1 = G – 1

Now let’s add 1 to each side again.

2G + 2 = G

Now let’s subtract G from each side.

G + 2 = 0

Finally, let’s subtract 2 from each side.

G = -2

…which implies that B = -3. So this particular family has negative two daughters and negative three sons.

Either the family is composed of antimatter, or my ability to do really simple algebra is gone, or there’s some subtle trickery in the wording of this puzzle that I’m missing. For example, maybe the trick is hiding in the difference between the words “and” and “as”: “each daughter has the same numbers of brothers and sisters,” while “each son has twice as many sisters as brothers.” The first sentence could be parsed to mean, “Each daughter has the same number of brothers-and-sisters (i.e., siblings) as the other daughters do,” which is trivially true no matter how many sons and daughters there are. But that reduces the system of equations to just:

2G = B – 1

which has infinitely many solutions for G and B. So where’s the error?

Update: I’m an idiot, as pointed out (gently) in the comments. “Each son has twice as many sisters as brothers” doesn’t mean

2G = B – 1

it means

G = 2(B – 1)

So the family is made of ordinary matter after all.

Corporations are not people

Corporations are not people, yet as “juristic persons” they enjoy many of the same protections that our government “of the people, by the people, for the people” grants to people. At the same time, they suffer fewer of the penalties. How do you incarcerate a transgressing corporation? Why are people subject to capital punishment and corporations aren’t?

It’s hard to pick the greatest threat to the American idea right now, but the lopsided power of amoral corporations is certainly on the short list. They profiteer from war, they mute our public discourse, they produce unhealthful things in unhealthful ways and then use corporate Jedi mind tricks to get us to buy them.

People have a time horizon of a generation or two: they want to leave a better world to their children and grandchildren and are willing to sacrifice in the short term to make sure of it. But even conscientious corporations are required to focus only on the next few fiscal quarters. Taking a longer view — not maximizing profits right now — risks a shareholder lawsuit.

On the other hand, there has never been a greater engine of prosperity in human history than the modern corporation. It’s easy to demonize corporations for the evils they cause — but it wouldn’t be so easy without the comforts they also provide.

Here is why John Edwards is my choice for president: he alone is dedicated to standing up to the power of big corporations. He alone has the paper trail to prove it’s not just campaign bluster. He alone has announced a plan to make corporations play fair. Yet he’s a corporate player himself — not a frothing, dogmatic anti-capitalist — who understands their underlying value.

When words meet faces

[This post is participating in The House Next Door’s Close-Up Blog-a-thon.]

For my money, of the many fine uses of closeups in cinema, the most affecting are the ones that focus the viewer’s attention on one person’s wordless reaction to another person’s speech. In this post I’ll describe three such scenes. (Spoilers ahead, for three old movies.)

Near the end of Mary Poppins, George Banks gets a phone call at home. Earlier that day, he’d brought his children with him to see where he works: a big bank in London, where he is a junior partner. He tells them, “A bank is a quiet and decorous place so we must be on our best behavior.”

Taking his children to the bank was not his idea. George Banks is one whose notion of fatherhood involves a lot of what today we’d call outsourcing — to his wife, to his nanny, to the rest of his domestic staff, even to the local constable when necessary. In his introductory scene he sings about his ideal day: “It’s six-oh-three and the heirs to my dominion are scrubbed and tubbed and adequately fed. And so I’ll pat them on the head and send them off to bed. Ah, lordly is the life I lead!”

No, taking little Jane and Michael to the bank was the result of some psychological jujitsu by Mary Poppins, who seemed somehow to know precisely the trouble that would ensue — and how it would ultimately heal the Banks household.

Jane and Michael’s introduction to Mr. Dawes, the bank’s senior partner, goes disastrously. Michael refuses to let Mr. Dawes see the twopence he’s brought, which farcically precipitates a run on the bank. “Stop all payments! Stop all payments!” shouts a harried bank officer. Clerks scoop up cash and coins and hightail it to the vault. Word spreads fast and a mob throngs in from the street outside.

Later that night comes the phone call. It’s the bank. George is to report to a late-night meeting where it is understood he will be summarily discharged. He hangs up and collapses into a chair. “A man has dreams of walking with giants,” he sings morosely, “To carve his niche in the edifice of time. Before the mortar of his zeal has a chance to congeal, the cup is dashed from his lips, the flame is snuffed a-borning, he’s brought to wrack and ruin in his prime.”

Fortunately, Bert the chimney-sweep is there, cleaning up from some mayhem earlier that evening. As he sings the following ironically to George Banks, the camera lingers on Banks’ face:

You’re a man of high position, esteemed by your peers. And when your little tykes are cryin’ you haven’t time to dry their tears and see them grateful little faces smilin’ up at you because their dad, he always knows just what to do.

You’ve got to grind, grind, grind at that grindstone though childhood slips like sand through a sieve. And all too soon they’ve up grown and then they’ve flown and it’s too late for you to give just that spoonful of sugar to help the medicine go down…

I watched this recently with my three-and-a-half-year-old son Archer, who is extremely chatty when watching movies. He continually asks for commentary on the action in the film, even when it’s extremely obvious and he understands it perfectly well. (“Why did Robin climb down that ladder?” “To hand Batman the can of Shark Repellent Bat-Spray.” “Why?” “To make the shark stop biting Batman’s leg.” “Why?” “Because would you like a shark biting your leg?” “No.” “That’s why.”) We encourage this, because it turns what would be a very passive, brainless activity into an interactive, enriching one.

On this occasion, as realization crept over the sad face of George Banks, Archer asked me, “What is happening?” With a lump in my throat I answered, “He’s realizing for the first time how much he loves his children, and that he hasn’t been a very good daddy.” (Yes, I get a lump in my throat watching Mary Poppins. So sue me.)

To cap it all off, Banks’ children shuffle contritely into the room, offer a sweetly sincere apology, and place in his hands the troublesome twopence. Wonder, sorrow, admiration — it’s as if he’s seeing his children for the first time, and it’s all right there on his face. And could that be a glimmer of a new lightness in his heart?

Some emotional moments are too profound for words. Archer seemed to sense this too and remained uncharacteristically silent for the next several minutes as George Banks grappled with a rearrangement of his worldview. For all the music and color and whimsy in this film, this one little moment was its dramatic climax. It was the perfect use of a reaction closeup.

I am no Bette Davis fan. But she delivers an amazing performance in Frank Capra’s final film, Pocketful of Miracles, and does much of it with her amazing, aging face.

In the film, she’s Apple Annie, a gin-swilling panhandler on Depression-era Broadway. She’s a tough old broad but she has a secret soft spot: she adores her daughter Louise, who has lived abroad all her life and knows nothing of her mother’s true nature. Annie has maintained a deception in her lifelong correspondence with Louise, claiming to belong to New York’s high society. Now Louise, grown into a beautiful young woman, writes that she is engaged to marry a Spanish nobleman — and they are coming to New York to receive her blessing!

Annie wanders the city in a daze. What can she do? She longs to meet her daughter and hold her in her arms, but she is ashamed of herself, afraid of what Louise will think, and fearful of causing Louise’s fiancé to break the engagement.

Fortunately, an important local gangster (with a heart of gold), Dave the Dude, has his own soft spot — for Annie. He believes that her apples bring him luck, and he never does business without first buying one from her. Now he’s due at his most important meeting yet, with a major mob boss from Chicago. But Annie is nowhere to be found.

Annie’s fellow panhandlers (who have known about Louise all along and have learned about Annie’s dilemma) find Dave and bring him to Annie’s pathetic little tenement, where she is out of her mind with worry, and drunk to boot. They tell Dave about Annie’s daughter and plead with him to help her. Dave interrogates Annie skeptically, all impatience. He just wants to buy an apple and get to his big meeting. He doesn’t have time for this. Annie just overdid it on the gin again, that’s all.

As Dave the Dude rails insensitively against the story the panhandlers tell him and what they’re asking him to do, the camera is tight on Annie’s miserable, besotted face. The shame, fear, and desperation in that face build to a piteous crescendo, more vivid than any mere dialogue could have made it. She doesn’t want Dave to see her like this, she doesn’t want him to know her secret pain, and his brusque manner isn’t making anything easier. When he finally spots a photo of Louise and demands, “Is this your kid?” Annie denies it. An instant later her heart breaks as he tosses the picture frame aside — and the truth is out.

The cops are closing in on Ned Racine, and he knows it. Worse: the cops are his friends. From them he learns that a crucial piece of evidence in a murder case is the victim’s missing eyeglasses. If they can be found, it should clinch the case — and put Ned in jail, because he’s guilty of the crime.

In Lawrence Kasdan’s noir homage Body Heat, a masterpiece in its own right, Ned has conspired with his mistress, Matty Walker, to kill her rich and distinctly unlikeable husband. Ned, a crummy defense attorney, learns from one of his recidivist clients, Teddy, how to create an incendiary device with a timer. With it, Ned obliterates much of the evidence (including the dead body).

Now his client warns him that a tall, beautiful brunette came around asking him how to rig such a device to a door. Ned is stunned. Could that have been Matty? Who else would have known to ask Teddy about such a thing? Why would she need another bomb? Why wouldn’t she tell Ned?

Then Ned gets a call from Matty, who’s out of town. I know where the glasses are, she tells him. The housekeeper was blackmailing me with them. I paid her off. She put them in a drawer in my boathouse. You should go and get them right away.

As Ned listens to Matty’s lies, the camera closes slowly on his face. His cigarette burns forgotten almost down to his fingers. He grunts his monosyllabic responses, but his face says everything that really matters. She wants me dead. She wants all the money for herself. She wants no witnesses. I’ve been a fool.

Save the world again with Admiral Bob

When I wrote my blog post, “Save the world with Admiral Bob” recently, I had no idea that a few weeks later it would be Blog Action Day, nor that the topic of this Blog Action Day would be “the environment.” But I found out just in time to participate, so for this Blog Action Day I would like to (re)invite you to read my recent post, “Save the world with Admiral Bob.”

When I wrote my blog post, “Save the world with Admiral Bob” recently, I had no idea that a few weeks later it would be Blog Action Day, nor that the topic of this Blog Action Day would be “the environment.” But I found out just in time to participate, so for this Blog Action Day I would like to (re)invite you to read my recent post, “Save the world with Admiral Bob.”

The guy from the old wine commercials

Recently I came across this photo online of a young Orson Welles and immediately saw (a broodier, better-dressed version of) myself.

Recently I came across this photo online of a young Orson Welles and immediately saw (a broodier, better-dressed version of) myself.

It’s not that I’ve ever identified with the guy; certainly not with the suicidal, scorched-earth attitude with which he went after William Randolph Hearst, who promptly and predictably squashed his career like a bug. And I’m on record as saying that Citizen Kane, while clearly an important and innovative landmark in filmmaking, doesn’t hold up as well as its perennial “best movie ever made” accolades would have you believe. (As all right-thinking people know, the real best movie ever made, the one that does hold up well decade after decade, is The Godfather.)

No, I just saw a striking physical resemblance. At once I mailed this photo to family and friends. “Don’t you think this looks like me?” I wrote.

Everyone thought I was crazy. No one thought it looked remotely like me.

It just goes to show you. I’m not sure what it goes to show you, but it does go to show you something.

Target acquired

We didn’t go to see the Blue Angels on Saturday as originally planned. Too much else to do around the house, and Archer and I were both still recovering from being sick earlier in the week. Going into the city to see the Blue Angels is a major production, between the parking hassles and the crowds. We just weren’t up to it. Plus we were in the middle of a major reorganization of the house, with the kids graduating from toddler beds to bunk beds!

On Sunday, the last day of Fleet Week, we planned to skip the Blue Angels again for the same reasons. But we ate lunch out, and after we finished and emerged into the sunshine, we marveled (knowingly) at the gorgeous weather and decided on the spur of the moment to try to catch what glimpses we could of the air show.

It was already 2:15 and the show was probably already in progress. We knew we had no hope of parking anywhere, but we could at least drive back and forth over the Golden Gate Bridge and see a little bit of the performance from that vantage point. And that’s exactly what we did. Here and there we got brief, distant looks at close-formation flying over San Francisco Bay, heart-stopping dives toward the water, and multi-colored smoke-trail designs. Even at a distance, and even without the spine-rattling flyby engine roar, it was cool, if a bit of a letdown. We promised ourselves not to miss them again next year.

For the next fifteen minutes we drove back up 101 to go home. Jonah dozed. We got off the freeway, navigated the usual maze of local streets, and rode up the middle of the little valley where our house sits. Surrounded by hills on three sides, a lot of the sky is blocked from view.

And yet! We parked the car in the driveway, shook Jonah awake, gathered lunch leftovers and other items from the car, closed the doors, and stumbled lazily up our front steps, when we abruptly heard a growing, almighty roar. We all looked up, and an instant later were treated to the dazzling spectacle of all six Blue Angels appearing over the hill to our west! They screamed directly overhead in a tight delta formation, disappearing a moment later behind the hills to the east.

They followed us home! The uncanny timing and positioning of the flyby can mean only one thing: the Navy knows I’m onto them.