When John McCain and Sarah Palin win the election and then finish off the destruction of the planet that Bush and Cheney began, will you be able to say that you did everything you could to stop it? Did you give the maximum allowed by law to the Obama campaign? Did you register voters? Did you work the phones or knock on doors canvassing for votes? Did you change any minds? Or were you too busy shopping and watching TV? Was it a good movie? One where the hero saves the world and you thought, “Wow, if only I were cool enough to save the world”?

I hate people

Rolling Stone ran a feature on their website recently: “The 25 Funniest Web Videos (No, Really!)” First on their list: “Fat Kid on Rollercoaster,” from Australia’s Funniest Home Videos.

It’s fifty-seven seconds of hell. The camera is tight on two rollercoaster passengers. One is in extreme distress, pleading for help as he suffers unending pain and terror from which he cannot escape. His tormentor sits at his side, cackling with delight. A canned laugh track perfects the horror.

I am not exaggerating. See for yourself, if you can stomach it.

Enough people saw humor in that video that it made the Rolling Stone list and earned a lot of defenders in the online commentary, where a few folks who still have some common decency (“I don’t see what’s so funny”) expressed their dismay at those who found it funny (“Lighten up, it’s a terrified fat kid now being endlessly humiliated, haw!”).

One gets the impression that the common-decency folks are in the minority. Which explains much about the state of the world.

Mind like a steel sieve

This past weekend we took a family roadtrip to L.A. to see my dad and his wife, who were passing through, and to see new (but fully grown) family member Pamela, and to visit Disneyland once again, which we were not originally going to do but which we decided almost at the last minute we couldn’t not do while so close.

Friday night we ate dinner at Pirate’s Dinner Adventure, where actors and actresses who are waiting for their agents to get them better gigs (but are none the less enthusiastic, ’cause you never know who might be watching) perform a musical acrobatic pirate comedy aboard an elaborate pirate-ship stage while you eat your dinner and are occasionally called upon to participate. It’s just a few doors down the road from Medieval Times — same idea, but with knights and horses. Since seeing it depicted in The Cable Guy, I’ve wanted to try a medieval-style dinner, with no utensils for your mutton leg and nothing but mead to drink. I said as much as we sat down to the pirate dinner and Andrea told me, “We did that years ago at the Excalibur in Vegas.”

No way, I said. She described some details from it. You’re making that up, I said. I had absolutely no memory of it. But I knew she was right, because she always is about this sort of thing. Try as I might, though, I could not conjure any genuine memories of that dinner show. I could remember plenty of other details from that Vegas visit and others, but that entire experience, which I fully acknowledge did happen, is a complete blank.

Why? I have no idea. If I did drugs or drank to excess, that might explain it; but as is almost always the case, I was sober as a judge. If I were a seriously sleep-deprived new parent, that might explain it, but this was years before kids. No, I simply don’t remember it. I remember Siegfried and Roy, I remember Penn and Teller, I remember David Cassidy, Lance Burton, Wayne Newton, and two different Cirque du Soleil shows, but for no discernible reason, not that one.

Which raises the question: what other episodes from my life are missing? At least I haven’t ever woken up next to a dead hooker. I think.

The worst form of government except for all those other forms

When Barack Obama becomes President of the United States — there’s no point saying “if,” because if he loses, then what John McCain will be president of won’t really be the United States any longer — things will start to get better. Almost certainly not fast enough, and some things will have to get worse before they get better, but at least things will start to get better.

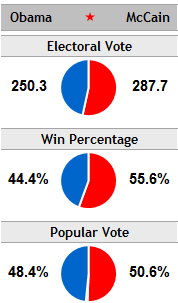

However, nothing can fix the fact that in 2000, the American people did not revolt when the Supreme Court halted a legal recount and handed the presidency to George Bush on the flimsiest of pretenses. Nothing will change the knowledge that in 2004, after things had already gotten terrible, America re-elected Bush because they were persuaded by repeated insinuation that John Kerry was a flip-flopping coward from France. And there’s no erasing the fact that Obama is running almost neck-and-neck with a lying, hateful, ill-informed, septuagenarian, unhealthy, misogynist warmonger and his lying, vindictive, ill-informed, unpatriotic, thieving, scandal-plagued running mate.

America, WTF? Yes, we’ve all imagined our own versions of the strangely familiar feel-good comedy that ensues when McCain croaks and Sarah Palin has to step into the Oval Office to become the sassy, brassy commander-and-working-mom-in-chief. She’ll give the world some tough love and a dose of what it really needs, right?

Wrong. If you really want to see that, that’s what we have Hollywood for. The election is about people’s lives. It’s about the fucking qualifications.

Writing advice

My young cousin Matt is applying to college and I was enlisted to help edit his admissions essay. In the process of doing so I came up with these pieces of (debatable) wisdom about how to write well.

If I had to give just one piece of overriding advice for writing well, it’s this: place yourself into your readers’ shoes. Imagine what they’re thinking while they’re reading your words. Anticipate their questions, their confusion, and their boredom, and then prevent them ever feeling those things.

If you then allowed me to give a second piece of advice, it would be to liken a newly written essay to a block of marble. Somewhere in there is a beautiful sculpture waiting to come out; your job is to remove the extraneous bits that are hiding it. As the writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry said, “Perfection is achieved not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.” Often the hardest part of writing is looking at a great sentence you’ve composed, full of well-chosen words, and realizing it contributes nothing other than to show off how flashy you can be. You’ve got to rip those out without mercy.

As you then ran screaming from my attempts to give a third piece of advice, I would shout after you, “When you pile too much into one sentence, it’s easy to get bogged down in trying to untangle its twisty, complicated structure, when the better remedy is so simple: just break it up into two sentences! Matt! Maaaaaatt!”

The mind of a (darnedest) empiricist

Earlier this summer I took Jonah to a birthday party at a local park. At one point I found him strolling with his friend Jude, each of them holding wads of paper napkins, dripping wet. On closer inspection I could see that the napkins were wrapped around pieces of ice they’d taken from the beverage cooler. I asked Jonah what he was doing.

“I’m trying to make dry ice.”

8/8: lines about a 44 woman

It’s 8/8/08, the day Julie Epelboim would have turned 44. 4+4 is 8. 44 is half of 88. Julie was born on 8/8/64, and 8×8 is 64.

I mention these things not to be glib about my friend who succumbed to cancer at age 36 (which is 44 minus 8), but because she would have taken delight in these simple number patterns. I still remember how excited we were when she turned 24 (which is 8+8+8) on 8/8/88.

Yes, we were nerds, but that was the whole point. It was my great good fortune to befriend a smart, sexy girl who was actually attracted to math nerds. What would I have done otherwise?

It happened like this. When I arrived in Pittsburgh I was three hundred or more miles away from everyone that I knew, the state’s motto — “You’ve got a friend in Pennsylvania” — notwithstanding. I spent a few days envying the busy social life of my roommate Joe, who was a Pittsburgh native. Classes had not yet really gotten underway and there was little to do other than attend a few orientation events, buy textbooks and supplies, and feel lonely.

Finally I set out for campus one afternoon with the specific intention of making some new friends. Pretending to be confident, I spotted a group of freshmen chatting in the student center, listened in on their conversation, and broke into it at the first opportunity. One of the freshmen was Julie; another was David, her brand-new boyfriend. A third was Julie’s roommate Michelle, whom I dated for a couple of months. For a while, she and I and David and Julie were an inseparable foursome. Later, Michelle was out of the picture but David, Julie, and I continued to have adventures together of various kinds.

Time passed. I’d come to Carnegie Mellon to learn computer science, but after three semesters I still hadn’t had any computer classes. (I’d aced the first-ever Computer Science AP exam in 1984 and so placed out of CMU’s introductory courses.) So by the fall of 1985 my interest in school was almost nil and my grades showed it. I was placed on academic suspension! I remained in town, though, taking a class and a part-time job at the University of Pittsburgh down the road and keeping in touch with my friends. During that time I contemplated a career as a writer rather than as a computer scientist, and in fact I applied to transfer to Hampshire College, a liberal-arts school in Massachusetts.

But then two things happened. First, David and Julie, still together after more than a year, had hit a prolonged rough patch in their relationship. Julie started spending more of her time with me, her oldest other college friend. Suddenly, thanks to the magical power of alcohol, one night we were fooling around, and in the following days and weeks we kept it up. I hated cuckolding my friend but it was just what I needed.

Second, thanks to spending more time with Julie, I was exposed to Carnegie Mellon’s first wave of non-introductory computer-science courses, which she had finally reached. I helped her often with her homework. By the time I heard from Hampshire College admissions — my application was approved! — my enthusiasm for computer science had returned with such vigor that I was able to talk the dean into ending my suspension a semester early. That fall I was a CMU computer science student again and kicking academic ass.

Julie helped to ensure my life turned out the way it has in a variety of ways. Getting me back into computer programming was one. Being the reason I met Steve — my friend, frequent co-worker, and future business partner — was another. Her perspective on the world — she’d grown up in Moscow, which was unspeakably exotic to me — broadened my narrow one.

None of which is to overlook her other important contribution to my future: in a word, sex. Andrea won’t like my recalling this so publicly (or, really, at all), but the fact is that if it hadn’t been for Julie, then by the time I met Andrea I would still have had too many wild oats left to sow. We could never have built the life together that we have.

In fact I started becoming friendly with Andrea around the same time that my friendship with Julie was winding down — that same summer of ’88, when Julie turned 8+8+8, we all graduated, and she made plans to leave Pittsburgh for grad school in the fall. (By then I was employed by CMU and remained for another four years.) On the one or two brief occasions that their paths crossed, Andrea, sensing my fondness for Julie, regarded her askance. (Andrea’s dog, Alex, must have picked up on her coolness toward Julie, for when Julie made a surprise visit a couple of years later to attend a housewarming party we were throwing, Alex — who loved everyone, sometimes to a fault — immediately began snarling at her!)

More time passed. Julie got married, had a son, earned a doctoral degree. Andrea and I moved to California and had our own adventures. I remained in occasional e-mail contact with Julie; once in a while we’d forward one another something funny from the web, or something nostalgic, such as when someone else had the idea of naming a computer matchmaking service “Yenta.”

I think it was late 1999 — when Andrea and I finally got married, incidentally — that I learned Julie was having some medical problems, apparently a complication from the Crohn’s disease she’d suffered most of her life. When I corresponded with her again a few months later I was dismayed to learn her problems were continuing. By the fall of 2000 she was fighting a major cancer battle. To her lasting credit, Andrea urged me to visit Julie in Maryland where she was hospitalized in an ultra-sterile cancer ward getting powerful chemo treatments.

I spent a few days chatting with her, reading to her, running errands for her and her family, removing myself when the doctors wanted to practice medicine on her or when the drugs — Gemzar and Taxotere, I somehow remember very clearly — made her too sick to tolerate company.

She was brave and in good spirits but confided in me toward the end of my visit that she didn’t think she’d win the battle. By that point she’d been released from the hospital, I’d helped her family get her settled back at home, and I thought things were looking up for her. Her flat self-prognosis frightened me, so I put on a brave face, pooh-pooh’d her pessimism, and promised her what ongoing support I could.

After I got back to California I sent her a postcard or a letter about once each week on any random subject to keep her connected with the living world. The then-current Florida election struggle was a frequent topic. After a while I started to get miffed, in spite of myself and of knowing what she was going through, that she hadn’t sent a reply — hadn’t even dictated a postcard — even once.

On January 13th I got a call from David. Julie and her family had traveled to Mexico for some promising cancer treatment that was not yet FDA-approved, so not available in the U.S. While there she slipped into a coma from which she never awoke. She was dead.

The news knocked the wind out of me. I spread the news to some friends and they were likewise crushed. I sent these condolences to Julie’s parents, whom I’d known and admired for almost half their daughter’s life:

The last communication I had from Julie was when she left a very garbled (because of cell phone interference) message on my answering machine around Thanksgiving. I couldn’t make out much of what she said, but it sounded like she was calling the people she felt thankful to have in her life. That message, and some of the things she said when I visited her, make me feel certain that, though she had to endure a terrible ordeal, she knew she was surrounded by many people who loved her. She was thankful for my friendship — and I was only the least of a generous phalanx of very supportive friends and relatives.

Julie should have had a much longer life, but it seems to me she could hardly have hoped for a better one. She enjoyed academic and professional success; had an amazing family and true friends who genuinely cared for her; raised an incredible little boy who has wit, intelligence, and a disposition far beyond his years; and had lots and lots of fun.

Julie was my companion during the time in my life that I was growing from a provincial, pretentious kid into a mellow, mature adult. I learned a lot from her and remain surrounded by numerous reminders of how she helped me to become who I am. In a very real sense, she left a part of herself with me, and as long as I’m drawing breath, that part of her will live, too.

It’s hard to imagine now, but once upon a time, before Revenge of the Nerds, the old stereotypes about nerds were largely true: socially inept, unworldly, preoccupied with abstractions and fantasy. Julie was the first person I’d ever met who had one foot in that world — we debated Star Trek and played Rogue together — and one in the world of finer things: good food (we dined out many times on her aunt’s credit card), poetry (in high school she’d written a truly affecting love poem to resemble a program in the computer language BASIC), animals (her cat won awards at purebreed shows), but mostly other people. Today most “computer nerds” can probably be said to have a greater, healthier breadth of interests than in the past. I certainly do. Julie was the prototype.

Matchmaker, part 2

Shortly after arriving at college and resisting the lure of fraternity life, I found myself wanting to participate in some organized student activity and so joined the school’s entrepreneurship club. I had the idea that if my computer dating “booth” had been a success in high school despite the small student population, their sexual immaturity, my crappy questionnaire and slow software, and the technical problems I’d had, it should be easy at college to improve on all those problems and repeat that success — and this time, I could make money from it.

(I spent more time thinking about business schemes [and girls] when I got to college than I did about my schoolwork. One idea was for a service that would deliver food from local restaurants to starving students sick of the slop they served us at the Kiltie [“kill-me”] Cafe. My plan never got off the drawing board, but the time must have been right for that idea because within a couple of years, several cities had exactly that. It wasn’t the first time I had an idea that I didn’t capitalize on, and that others later did. Pittsburgh’s restaurant-delivery service was called Wheel Deliver. One of the agents who worked the phones there was named Andrea. “And today that woman is my wife.”)

I got to work writing a new version of the matchmaking software, this time in Turbo Pascal on an IBM PC, hundreds of times faster than the version that Chuck and I had written in BASIC on the Sol-20. My new friends David and Julie (yes, the same David and Julie) helped me to design the questionnaire. It was still two years before the birth of desktop publishing so everything was typewritten or hand-lettered. The master copy of the questionnaire was literally cut-and-pasted together from dozens of bits of paper.

I took some of my $300 budget and headed to Kinko’s, where I ran off reams of copies of the questionnaire and some teaser posters I had conceived as the ad campaign:

The name, Yenta, was taken from the matchmaker’s name in Fiddler on the Roof. I stapled those posters all over campus and managed to create some “buzz.”

Meanwhile I needed to find someone with a computer and a printer I could use when I set up the station for running off customers’ result lists. In 1984 those were still pretty hard to come by. I allocated another $50 as incentive and placed an ad on the campus bulletin board. The taker was a fellow freshman named Bruce, who took my $50, loaned me his equipment, and became a lifelong friend. (A few years later, I visited him often in the house he shared with my other friend, Steve. The house was divided into two apartments. One day on my way to visit Bruce and Steve, I met Andrea, the downstairs tenant. “And today that woman is my wife.”)

Once we had the needed equipment we ran off another batch of posters telling people what Yenta was and to check their campus mailboxes for questionnaires, to fill them out and turn them in by such-and-such a date, and to show up at the student center during certain hours on certain days to collect their match results, just five dollars for a printed list.

The response was good enough to require multiple miserable late nights of tedious data entry, which was all too familiar to me but new to David and Julie, who had become my equal partners and shared much of the burden. At the appointed times we set up Bruce’s computer in “Grey Matter” and served our customers. It all went very smoothly.

In the end, Yenta made a profit of around $900, which David and Julie and I split. It was the most successful venture in the entrepreneurship club that semester, and I parlayed my success into a date with the club’s president, a sophomore named Robin who was a Tri-Delt, a sorority about which I had heard some exciting rumors. The date was disastrous, however, which I guess you can take as a comment on the fallibility of computer matchmaking, sort of.

(To be continued…)

To the nerdth power

Nerd confession: I just realized that my son Archer, who is 4, and my stepdaughter Pamela, who just turned 27, both have ages that can be expressed in the form nn — Archer is 22 and Pamela is 33. Barring a major advance in gerontology research I regret to say it is unlikely any of us will ever see 44.

Nerd confession: I just realized that my son Archer, who is 4, and my stepdaughter Pamela, who just turned 27, both have ages that can be expressed in the form nn — Archer is 22 and Pamela is 33. Barring a major advance in gerontology research I regret to say it is unlikely any of us will ever see 44.

(Didn’t know that I had an adult stepdaughter? I haven’t mentioned her here before, but we added her to the cast a couple of seasons ago in a Cousin Oliver moment to boost our sagging ratings.)

Update: Oh drat, Pamela’s 26, not 27. What’s interesting about the relationship between her age and Archer’s now? Umm… Archer’s is the number of suits in a deck of playing cards, and Pamela’s is the number of red (or black) cards? Sorry, that’s the best I’ve got.

Another day in the nation our fathers fought and died for

Newly reported this day in The Country Formerly Known As The Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave:

- There is a growing mountain of evidence to suggest that the anthrax attacks that followed on the heels of 9/11 were orchestrated from within our own government to cement the public’s fear and distrust of Islam and propagandize for war with Iraq.

- We are prisoners within our national borders, except for those willing to surrender their privacy, their property, and their right to due process.

Just one day in Bush country. (Another recent day.)

About the anthrax attacks: Glenn Greenwald (the superb Salon.com reporter whose column I linked to above) points out that the anthrax/Iraq propaganda campaign — which is fact, not surmise; the falsehoods involved have been exposed and not refuted — was carried out by multiple “well-placed sources” feeding misinformation to ABC News, which repeated the talking points so faithfully that it became ingrained in the national discourse.

This put me in mind of a story that Larry Flynt told in an interview a few years ago (coincidentally also in Salon.com — or not so coincidentally, considering how few good, independent news outlets there are):

In 2000, I got a call from a lawyer in Houston. He told me that his client, “Susan,” could prove that George W. Bush arranged for his girlfriend to have an abortion back in the early 1970s. Her boyfriend at the time, “Clyde,” was pals with Bush and set up the procedure. We checked up and found that indeed “Clyde” was responsible for keeping Bush out of trouble. Bush had knocked up a girl named “Rayette.” We talked to the doctor that performed the abortion. We felt we really had a blockbuster story, but about two months before we were going to break the story, “Susan” disappeared. We finally found her. She was living in a half-million-dollar home in Corpus Christi, Texas. Before that she was living in a small apartment working for $13,000 a year as a cocktail waitress. I’m not saying Bush bought her off, but I’m confident that one or more of his cronies did. The only thing that interested me in this story is — I’m pro-choice, but to have a guy who is running on a pro-life platform… and this procedure was committed in 1971, two years before Roe vs. Wade, which would have made it a crime.

I went to two members of the national press (during the 2000 presidential campaign) and said, “Look. I don’t have anyone out on the stump. You guys do. At least ask Bush the question.” You know what? They refused to. One of them had the nerve to tell me that the election was too close. “We don’t want to be the ones to tip it in any direction.”

“We don’t want to be the ones to tip it in any direction” — as if by withholding the news they somehow weren’t doing exactly that.

I can almost identify with what that reporter told Flynt. Early in my career as a computer programmer I occasionally soliloquized about my unwillingness to work on anything much more mission-critical than e-mail software. “I could never write medical software,” I’d say, “or flight-control software, or anything like that. If there’s a bad bug in my code, the worst that happens is that someone loses some personal data. They don’t die.” I found the very idea of that much responsibility appalling.

But guess what? Someone’s gotta write the mission-critical code. If I’ve got the knowledge and the access, it’s my responsibility to do it, because otherwise someone not as qualified might do it in my place and then I would share some of the blame for any critical failures anyway. On the flip side, who’s to say what’s mission-critical and what isn’t, even when it comes to e-mail software? It’s remotely conceivable that the loss of the just the wrong data at just the wrong time could cost someone his or her life — especially if some unscrupulous person (a war profiteer, say) had figured out a way to “game the system,” taking advantage of my desire to avoid responsibility in order to create a certain outcome.

The reporter who talked to Flynt was exhibiting the same fear of responsibility and was being gamed in just that way. But my (somewhat strained) point is that you’ve got responsibility whether you like it or not. You can’t avoid it; the best you can do is to refuse to acknowledge it.

I write software that people rely on; it’s my responsibility to make it reliable, whether or not it’s a matter of life and death. Those reporters in 2000 were part of a system on which a healthy democracy relies: keeping the citizenry well-informed, letting them decide whether a news item should tip a race one way or another. That was their responsibility; they blew it.

The same fear of responsibility is what leads modern news operations to present two sides of every issue as equal, when it’s perfectly obvious that they seldom are. It’s their responsibility to treat propaganda skeptically rather than presenting it on the same footing as legitimate news. When it’s decisively exposed as propaganda, it’s their responsibility to report on that.

That’s the responsibility that ABC News can now deny but cannot avoid: to disclose the identities of the propagandists who manipulated them and to shine a light on the whole operation. Until it does, ABC can deny, but cannot avoid, its responsibility for launching a war that has killed thousands, decimated our military, and bankrupted our nation.