It wasn’t until I happened to take my kids to the Two Niner Diner at Petaluma Airport for lunch this weekend that I realized an anniversary had almost passed by unnoticed — fifteen years, this month, since I earned my private pilot license.

Five years earlier, Andrea bought me an introductory flight lesson as a Christmas gift, knowing that I’d long dreamed of flying. As a kid growing up in Queens, I would take the bus to LaGuardia Airport to watch takeoffs and landings (in the days before the “land of the free and the home of the brave” decided it was too terrifying to allow anyone to do this and roped off all observation areas, sucking the last bits of glamor and romance out of aviation). I checked out FAA training manuals from the library and learned them. I became an expert in Microsoft Flight Simulator (which I started using in the days when it was still the subLOGIC Flight Simulator for the TRS-80).

In spite of all that, it had somehow never occurred to me to actually go and do something about learning to fly. It took Andrea giving me that certificate to get me in the air. So one cold day in January 1991 I drove to Phoenix Aviation (issuer of the gift certificate) at Allegheny County airport, and a flight instructor named Jay Domenico took me aloft in N6575Q, a bright yellow Cessna 152, and handed me the controls.

I was hooked, and I continued flight training at Phoenix with Jay. But between my meager finances, my job workload, and the unreliable weather around Pittsburgh, I didn’t train often enough to earn my license during the next two years, following which I moved to California to join a tiny software startup. The weather there was a lot more conducive to flying, but as often happens to those who commit themselves to tiny software startups, my available time and money dwindled to almost nothing.

By 1994 that situation had improved. I celebrated a successful major software release with a resumption of my flight training, and by September of the following year I’d passed my checkride and earned my license — just as enormously satisfying an accomplishment as you can imagine.

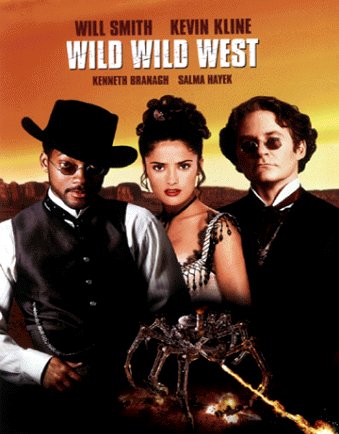

Circa 1998, ferrying friends Rob and Holly

to a so-called

$100 hamburgerin Columbia, California.

I used my license on only a handful of occasions over the next few years, renting a plane from my local flying club for a day trip, sometimes solo, sometimes with one or two friends or family members. No trip was longer than a couple of hours; each was memorable in a different way. A few highlights:

- My dad’s nonstop astonishment — and white knuckles — on our trip to Monterey;

- Leaving Petaluma on a perfectly clear morning with Andrea and returning late in the day to a giant dome of forest-fire smoke;

- Overflying Skywalker Ranch with my friend Steve, neither of us entirely certain that George Lucas couldn’t launch a squadron of TIE fighters after us;

- Strolling around the airport in sleepy Lakeport on my birthday, befriending some hangar-dwelling artists and helping ourselves to fresh-fallen walnuts from an orchard across the road;

- Landing in Fresno, discovering the airport restaurant had closed (for good), but being in luck anyway because a big public barbecue was under way in one of the hangars; later, flying home with a brand-new, honest-to-goodness cowboy hat from a nearby western-wear store;

- Best of all, sharing the controls on a trip to Harris Ranch with my childhood friend Chuck, who used to come with me to watch those planes at LaGuardia and who also earned a pilot license after moving abroad for college.

Private pilots must undergo so-called biennial flight reviews (at two-year intervals, hence “biennial”) to maintain the validity of their licenses; it’s sort of like having to take your driving test again and again if you want to keep driving (which wouldn’t be a terrible idea, if you ask me). Having earned my license in September of 1995, and having renewed my BFR promptly every other September after that, I had a BFR due in September of 2001. A few days before my appointment, some murderous idiots hijacked some jetliners and flew them into some landmarks, and all aircraft nationwide were grounded for a period of days. My BFR was canceled. When the opportunity arose to reschedule it, I didn’t — because by this point, Andrea and I were expecting our first child. I never thought of flying as an especially dangerous hobby, but it’s certainly more dangerous than not flying, and the prospect of new-parenthood was enough to ground me, at least temporarily.

That spring, Jonah was born, and two years later so was his brother Archer. It had been three years since I’d flown and I was missing it terribly. Worse, I knew that my flying knowledge and skills were decaying, and that it would take several hours of refresher instruction before I felt comfortable flying again by myself. With two young kids, a new job, and a new house, that simply wasn’t in the time or money budget, but I consoled myself with this plan: I would keep my flying ability secret from my kids, and then one day, when they were old enough to be properly impressed — around 8 and 6, I figured — I’d spring it on them, taking them to the airport and surprising them with a flight over the local area, their dad at the controls. By then I would surely have worked some refresher training into the budget.

Well, the kids are now 8 and 6 and there is still no flying in the foreseeable future. But they still don’t know their dad’s a pilot, and they still don’t read this blog, so the possibility still exists — though maybe not for long — that I can blow their minds someday.

Finally we arrived at Sonic Drive-In which, despite its name, we were surprised to discover actually was a drive-in. We pulled into one of the order stalls in the parking lot. The prospect of eating in the same car where we’d been entombed in traffic did not exactly appeal, so I opened my door to discover whether there was any indoor seating. I say I opened my door, but note that I didn’t say I stepped out of the car, since the stall’s menu and ordering station only allowed me to open it a few inches. Nevertheless I extruded myself through the narrow gap and scoped out the restaurant. There were some nice outdoor tables, but Andrea nixed those, insisting it would be fun to eat in the car, vintage-drive-in-style. “Fine,” I monosyllabled through gritted teeth.

Finally we arrived at Sonic Drive-In which, despite its name, we were surprised to discover actually was a drive-in. We pulled into one of the order stalls in the parking lot. The prospect of eating in the same car where we’d been entombed in traffic did not exactly appeal, so I opened my door to discover whether there was any indoor seating. I say I opened my door, but note that I didn’t say I stepped out of the car, since the stall’s menu and ordering station only allowed me to open it a few inches. Nevertheless I extruded myself through the narrow gap and scoped out the restaurant. There were some nice outdoor tables, but Andrea nixed those, insisting it would be fun to eat in the car, vintage-drive-in-style. “Fine,” I monosyllabled through gritted teeth.

the visually taxing menu myself through the red haze that filled my field of vision. Even now that I’ve long since recovered I don’t care to recall those few minutes, for me the low point of our outing. Finally we placed our order and I walked outside around the car, trying to breathe deeply from my center.

the visually taxing menu myself through the red haze that filled my field of vision. Even now that I’ve long since recovered I don’t care to recall those few minutes, for me the low point of our outing. Finally we placed our order and I walked outside around the car, trying to breathe deeply from my center. Things started to look up a very few minutes later when to our delight, our food arrived on a tray carried by a friendly woman on roller skates. (To be honest, the actual first gap in the storm clouds was when I spotted tater tots on the menu. Tater tots!) She hooked it onto an open window and we distributed our food items to one another and tucked in. At the first bite, Samuel L. Jackson sprang to mind —

Things started to look up a very few minutes later when to our delight, our food arrived on a tray carried by a friendly woman on roller skates. (To be honest, the actual first gap in the storm clouds was when I spotted tater tots on the menu. Tater tots!) She hooked it onto an open window and we distributed our food items to one another and tucked in. At the first bite, Samuel L. Jackson sprang to mind —