I don’t have the most widely read blog, but I do OK. I get several pageviews a day, amounting to thousands of pageviews since this blog has been up and running. Guess how much AdSense revenue I’ve earned in all this time? (Hint: see the title of this post.)

Category: personal

The Maggie Show

I was in an Olympic-sized indoor swimming pool. Also in the pool were my friend Maggie, and the actor William H. Macy. It was Maggie’s daytime TV aquatic talk show, broadcast daily from that pool, and Bill Macy and I were that day’s guests.

I was in an Olympic-sized indoor swimming pool. Also in the pool were my friend Maggie, and the actor William H. Macy. It was Maggie’s daytime TV aquatic talk show, broadcast daily from that pool, and Bill Macy and I were that day’s guests.

Macy did a watery reading of a David Mamet soliloquy or something. My shtick — a bit déclassé after Macy’s performance, but I gave it my all anyway — was to take the deepest breath I could (which, this being a dream, was supernaturally large), submerge my mouth, and blow into the water, producing a jet of bubbles and propelling myself backward, describing an erratic curve through the pool like that of a balloon losing its air.

As soon as the dream was over, I woke up. Even though it was only 4:30am, I was wide awake.

What does it mean?

One morning in the seventies

The instant before I was prepared to scream, “YAAAHHHHH!,” without looking in my direction, he handed down from the table a handwritten piece of paper. It said:

You forgot to:

- Flush the toilet;

- Wash your hands;

- Brush your teeth.

Thus did my dad cement in my mind another many years of certainty about the supernatural ability of parents to know what their kids are up to — something I’m now trying to get my own kids to believe.

Curiosity killed the camera

A couple of years ago, the hardware guru at work, Sue, let me sit at her workbench and use her tools to try to repair my Canon Powershot digital camera, a midrange point-and-shoot model. On powerup, a tiny servomotor was supposed to telescope the lens barrel out of the camera body (just as hundreds of models do). Mine had stopped operating smoothly. The barrel, or the protective shutter in front of the lens, would get stuck halfway through an open or close cycle. I’d already gotten an estimate on a professional repair that was prohibitively long and expensive. Might as well give it a try myself and, at worst, buy a new camera.

I thought that by disassembling it as far as the lens barrel, I might be able to dislodge any grit or whatever was blocking its smooth operation, provided it wasn’t actually an electrical problem in the servo or anything else. I took out the batteries, then started removing screws and laying them carefully on the workbench in a way that might allow me to remember how they were all supposed to be put back together. But I was only able to remove tiny bits of camera at a time. Dozens of removed parts later it still looked pretty much like a camera. It was like the dance of the seven veils.

Before long there were so many screws and bits of camera shell and buttons and retainer rings and spacers on the workbench that it was clear it would never all go back together. But I pressed on anyway out of stubbornness and curiosity. Until the camera blew up in my hands.

Yes, I had forgotten about the giant capacitor that powers the flash. It discharged painfully into my fingertips with a loud BANG, a tiny shower of sparks, and of course the magic blue smoke. And that was the end of that. Now a little pissed, I spent another minute or two manhandling the (now slightly charred) camera just to get a glimpse inside the lens barrel by any means necessary. When I finally ripped it apart enough, there appeared to be nothing obvious I could have done anyway to fix it. I swept all the pieces into the trash as the phrase, “No user-serviceable parts” repeated over and over in my head.

Die Weiße Hölle vom Panther Hollow

This is another story about a crisis in a snowy hollow with a male and a female friend.

This one takes place in the winter of 1984-85. I was a freshman at Carnegie Mellon and hung around a lot with my friend David (a different one) and his girlfriend Julie. One clear, cold winter night there was a social event for CMU freshmen: free ice skating at a skating rink somewhere in Schenley Park. David, Julie, and I joined scores of other freshmen in congregating outside Skibo (CMU’s meager student union building, replaced since then with a gigantic activity mecca) and walking about a mile and a half through the park to get to the skating rink.

Now, Pittsburgh is a very hilly city. Its topography is characterized by wide, deep ravines that criss-cross the whole area. The ravines serve as natural boundaries to Pittsburgh’s neighborhoods. They are so prevalent, and form such effective barriers to getting around, that the city of Pittsburgh (which was compelled to bridge most of them in several strategic points) is second in the world only to St. Petersburg, Russia, in number of bridges! Or so I’ve heard.

It was a very chilly and long walk to the skating rink. Once we arrived, I looked back and observed that the campus wasn’t very far away as the crow flies. But because there was a ravine between the campus and the rink, we’d had to go far out of our way to cross a bridge and then backtrack once we were on the other side.

I couldn’t really skate and neither could David or Julie, so at the rink it was a fun time of continuous near-falling and catching each other and crashing into things.

When we emerged, I looked across the ravine at the nearby campus, then at the flock of freshmen trudging the long way around, and thought, “Not me!” Always valuing the bold departure from convention (sometimes to a fault), I announced my plan to cut straight across the ravine to get back to campus. David and Julie were in.

We stepped over a small railing and immediately began descending the steep, lightly wooded hillside. Just a few yards from the well-traveled paths we left behind, we discovered that the snow was much deeper — up to our waists in some places. Soon we fell silent as we concentrated on safely making our way downhill. The snow and the steepness made it slippery, while hidden roots and bushes snagged our feet and made it more treacherous. In a few places we had to allow ourselves a controlled fall, catching hold of the next tree down.

Finally we were on the level floor of the ravine (called Panther Hollow). From down there we couldn’t see anything atop either side of the ravine, but we could see the bridge. Lacking any other reference, we made for the bridge’s far side.

As we crossed the center of the ravine floor, we sighted up and down the train tracks that bisected it and remarked on how remote it felt. It was dark, quiet, snowy, and a little eerie. We joked with Julie (who was Russian) about being in a Siberian wilderness rather than the middle of a medium-sized American metropolis.

We reached the base of the hill beneath the bridge and began to climb. Almost immediately we realized what a pickle we were in. As difficult as the downhill part of our trek had been, the uphill part was all but impossible. It was just as steep and just as slippery, and though there were plenty of handholds in the undergrowth, the undergrowth was buried beneath several feet of snow, and of the three of us, only David had gloves!

It looked like a long way up, and our hands were already aching with cold. David, a gentleman, gave his gloves to Julie (on whose small hands they did not “fit like gloves”). I also did my chivalric duty by climbing a few feet, getting a secure foothold, and then pulling Julie up, in alternation with David. Soon Julie was getting so much help this way that she relinquished the gloves; I got one and David got one. Our hands were numb.

It had been fun up to this point, but now we saw how easily it could turn serious. An unlucky fall. Frostbite. Our mood turned grim.

Halfway up the hill we reached one of the bridge’s stanchions: a vertical steel beam that disappeared into a cylinder of concrete embedded in the ground. David pulled himself up onto the concrete cylinder, whose top was level. There he pulled Julie up while I pushed; and then I followed. The three of us sat and caught our breath on that flat circular seat. The remaining part of the climb looked to be just as difficult, but it began to seem doable.

We resumed climbing. Nearer the top of the hill, the snow was less deep than it had been. The hill was less steep. Soon we didn’t need our hands to climb. And then we were walking normally. And then, at last, we were at the top.

The campus was nowhere in sight.

We were in a run-down residential neighborhood with street names we didn’t recognize. The bridge beneath which we’d been climbing was not the same one that we’d crossed at the beginning of the evening. We had no idea where we were or how we could have gotten there.

The Cathedral of Learning

But it didn’t matter; we were no longer in peril. We struck out in a random direction and, before long, through a gap in the houses, we caught a glimpse of the Cathedral of Learning — as good a navigational beacon as any in Pittsburgh. Aiming for it, we finally emerged into familiar territory: downtown Oakland, a ten-minute walk from campus. We ducked into the McDonald’s to warm up and get some chow, then walked home, elated about the adventure and its happy outcome.

My friend Julie died of cancer early in 2001 at age 36. Many months later it occurred to me to e-mail a version of this story to her mother, Olga. She’d always been very nice to me and I guessed she’d never heard it.

I heard back from Olga promptly. She reported that, earlier the same day, she’d sent e-mail to Julie’s old account, which still existed, asking for a sign that Julie was still somewhere thinking about her family. In another example of the way things work out, my message arrived ten minutes later.

[The title of this post is a reference to this film.]

A good day

An orderly transfer of power? No tanks rolling down city streets? Republicans in tears? Donald Rumsfeld facing war-crimes charges? Dennis Hastert finished? Katherine Harris ruined?

Good ol’ Constitution, maybe the last bit of life hadn’t been wrung out of you yet after all. Good ol’ voters, knowing when the country is in real trouble and needs your help.

Maybe I won’t have to flee to Amsterdam with my family.

Maybe we actually can restore our rights. Maybe we can heal the planet. Maybe we can get some accountability. Maybe we can govern with compassion.

Maybe we can wipe the smirk off George Bush’s face. Maybe we can tell Dick Cheney to go fuck himself. Maybe we can give them two years of heartburn and sleepless nights.

Maybe it’s OK now to take my family to Disneyland.

Nervous wreck day

I will be a basket case until the election results are in, after which I may continue to be a basket case or I may not, we’ll see. Meanwhile, if you are eligible to vote and have some incumbent Republicans to kick out of office, please go make ’em cry.

Ode to the Plate-O-Shrimp

“She may not look like much but she’s got it where it counts, kid.”

[Please excuse the rambling nature of this reminiscence.]

One Saturday night in 1986 I got a call from my friend Julie asking for help. She had taken the bus from CMU to the Monroeville Mall some ten miles away, had spent too much time shopping, and had missed the last bus back. Could I find some way to get her back to campus?

A taxi would have been unthinkably expensive. I knew only one person with a car: my friend Bruce. I called him to discover whether his Camaro was in working order at the moment. No luck. But he knew someone named Steve who had a car. So I gave Steve a call. I told him Bruce sent me and explained the situation, then asked: could he go rescue Julie? He couldn’t, but he was willing to let me borrow his car, which was incredibly generous considering we had never met.

I ran to his dorm room where he handed me the keys to his 1977 VW Rabbit. I thanked him profusely and found his car in the parking lot. First problem: it had a 5-speed manual transmission, whose workings I understood in theory but not in practice. (“In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice; in practice, there is.”) Second problem: it was dark, I had no light, and I could not find the ignition. Five frustrating, sweaty, cuss-filled minutes later I had the engine started and encountered problem three: I couldn’t find “reverse.”

I ran to his dorm room where he handed me the keys to his 1977 VW Rabbit. I thanked him profusely and found his car in the parking lot. First problem: it had a 5-speed manual transmission, whose workings I understood in theory but not in practice. (“In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice; in practice, there is.”) Second problem: it was dark, I had no light, and I could not find the ignition. Five frustrating, sweaty, cuss-filled minutes later I had the engine started and encountered problem three: I couldn’t find “reverse.”

It took several more minutes for me to figure out that in a 1977 VW, you push the shift lever down and back and right to get into reverse. All this time, Julie was waiting at the Monroeville Mall, not knowing whether help was on the way or not. (This was before ubiquitous cellphones.)

I eased the Rabbit out of the dorm parking lot and onto the street. Anticipating the stop sign a block away, I stayed in first gear, reluctant to shift. As I made my way through the streets I slowly became accustomed to the manual transmission. Much bucking and jerking later, I got onto the parkway and arrived at the mall, where I found a cold and grateful Julie waiting by the curb.

Steve and I became friends and he continued to be as generous with his car as he was that first night. I and others in our group borrowed it often.

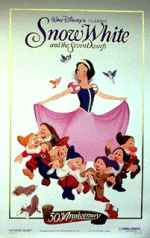

One hot summer day, Steve and I drove to New York in the Rabbit. An hour or two into the drive I began to feel feverish. By the time we neared Allentown, where we encountered bumper-to-bumper traffic, I was alternately burning up and shivering with cold. Then the car overheated and we had to pull over. We let the radiator cool, then opened it and found it empty. We had no water with which to refill it, so Steve struck off into the surrounding farmland to find some. Meanwhile, I unrolled a 50th-anniversary commemorative poster for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs that I was bringing as a gift to my mom in New York, turned it over, and wrote in big letters on the back:

One hot summer day, Steve and I drove to New York in the Rabbit. An hour or two into the drive I began to feel feverish. By the time we neared Allentown, where we encountered bumper-to-bumper traffic, I was alternately burning up and shivering with cold. Then the car overheated and we had to pull over. We let the radiator cool, then opened it and found it empty. We had no water with which to refill it, so Steve struck off into the surrounding farmland to find some. Meanwhile, I unrolled a 50th-anniversary commemorative poster for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs that I was bringing as a gift to my mom in New York, turned it over, and wrote in big letters on the back:

HELP

NEED WATER

Unfortunately my only writing implement was a ballpoint pen, so though I made the letters as big as I could and gamely tried to color them in, my sign was all but illegible to the endless line of cars creeping past only a few feet away.

The effort of lettering the sign wiped me out. The sun beat down. The traffic inching by spewed heat and exhaust fumes. No one stopped to offer help. I grew delirious. Suddenly there was Steve rolling an enormous black plastic barrel full of water. He’d stolen the barrel from some farm where no one was home, and filled it from a garden hose. We poured water into the radiator and placed the barrel in the back of the car, certain we’d need it again while stuck in that standstill traffic. (And we did, but Steve considerately let me swoon in the passenger seat while he did the hard work of coaxing the car back to life.) Eventually the jam cleared up and we got back onto open road, where sustained speeds above twenty miles per hour air-cooled our engine and kept our radiator water from boiling away.

On another occasion I borrowed Steve’s Rabbit just for the sake of having some alone time, driving some of the winding roads outside of Pittsburgh. On the parkway headed back to town, the transmission popped out of fifth gear. I tried to shift back into fifth but the shift lever wouldn’t stay. So I drove for a while in fourth, then that gear failed too. Still on the parkway, I switched on my hazard lights, moved to the right-hand lane, and continued in third gear as honking cars sped by me. When I got to my exit I lost third gear. Still a mile or so from home I lost second. With two blocks left to go I lost first gear too, but by an amazing stroke of luck I was just barely able to coast the rest of the way right into a parking spot on the street in front of my apartment, where parallel parking would normally be required but (by the same stroke of luck) there were no other cars in the way.

We later learned that while I was driving, a nut had fallen out of the transmission assembly allowing fluid to drain and causing the gears to grind themselves into slag one by one.

I promised to pay Steve for a new transmission, but he didn’t get one for a long time. The Rabbit sat unused awaiting its repair. Then one night at The Balcony, while playing the dice game Cosmic Wimpout, I won from him the cost of the repair! I subsequently bought the Rabbit from him for $25 and he bought me a new transmission. I christened my new car the Plate-O-Shrimp after a quote from the movie Repo Man. My sister Suzanne ever after referred to it (more accurately, it must be said) as the “Piece-O-Shit.”

The old transmission went into the hatchback — right next to the stolen barrel of water (still kept around just in case). One night inspiration struck. I bought some rope and, under cover of darkness, hoisted the old transmission into a tree on campus, tied it securely, and left it hanging like a strange grimy piece of metal fruit. Physical Plant cut it down some time the next morning, but not before my friend David, the art student, happened to see it. Years later, he told me it was one of the most artistic things he’d ever seen. I was flattered without really understanding what was so artistic about my silly prank.

Some time not long after that, my new acquaintance Andrea professed within my earshot a desire to learn how to drive a stick shift. Naturally I offered my help and my car. We took the Plate-O-Shrimp to a big empty parking lot on campus and she drove it around under my patient tutelage. “And today that woman is my wife.”

Eventually I started making some money and was able to upgrade to a less crappy car, a 1984 Corolla named the Fine Young Chap (which also needed a new transmission as soon as I bought it, but that’s another story). The Plate-O-Shrimp ended its life ignominiously: gifted to that same friend Bruce, it remained parked on a side street in Pittsburgh for so long that the police finally towed it away, never to be seen again — but never to be forgotten.

A class act

I got e-mail from Joseph Costanzo’s daughter the other day. She and her father happened on my blog post about him and (as she wrote in a comment) were moved. Yesterday I received from Mr. Costanzo a handwritten note and some news clippings about him, plus a copy of DiRONA 2006, a nationwide directory of superb restaurants (including The Primadonna, of course).

Joe Costanzo is a class act. The world needs him to reenter the hospitality business and blaze new trails, and when he does, I’ll be there.

Afternoon of the living(room) dead

One afternoon in the 80’s my friend Amy asked if I’d like to accompany her on an errand to the apartment of zombie-film director George Romero.

We were in college in Pittsburgh and Amy was housesitting for the famous filmmaker, auteur of the zombie classic (and disguised social critique) Night of the Living Dead and the other Pittsburgh-based “Dead” movies. Naturally I jumped at the chance to see how he lived.

It was an attractive but not especially distinguished apartment in an inconspicuous apartment building not far from CMU. In almost all respects it could have been the home of anyone who could afford the rent on a modest couple of hundred extra square feet of space. But three things about it were notable:

- The refrigerator was full of champagne, at least twenty bottles of the stuff.

- His vast collection of movies on VHS filled two walls of the living room. I drooled with envy as I read the titles. (Over the years, inspired by Romero’s living room, I too amassed a respectable collection of movies on VHS, or “Crapvision” as James Cameron famously called it. Within a decade those tapes grew all but unwatchable as the recordings decayed. Today you couldn’t pay me to store one tenth of Romero’s bulky old movie collection in my house. Funny how things change.)

- Several walls were cluttered with photos from the sets of his films. Many of those photos featured actors in full zombie makeup relaxing between takes. My favorite was of Romero’s young daughter Tina bouncing happily on the knee of one smiling, hideously decaying ghoul.