I don’t want to get myself in trouble, so right off the bat let me say that I am in no way likening myself to Jesus Christ. Yet when I think about a thing that happened to me in the summer of the year I turned eleven, I feel a certain kinship with him. And I don’t just mean being Jewish.

This story begins several months earlier, when I turned ten and received the most consequential birthday gift of my life: a portable Panasonic tape recorder.

Remarkably, a photo survives of me opening that gift. Clearly I am pleased.

You can draw a straight line from that moment to my participation as one of the founding members of the Internet Movie Database.

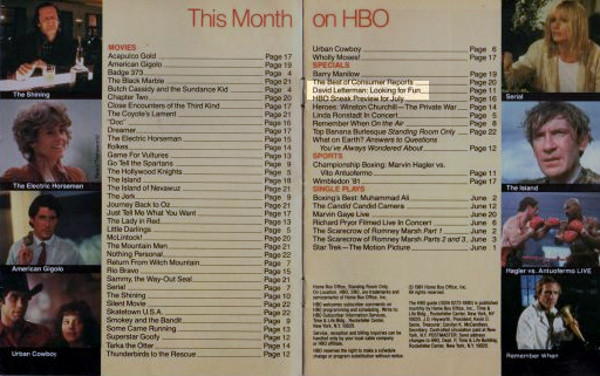

Like this: Around the same time, my family became one of the earliest subscribers to HBO. Home Box Office had the unique and, to a budding cinephile like myself, irresistible proposition in those pre-cable-TV days of showing movies uncensored and uninterrupted by commercials. Consumer videotapes were not yet a thing (much less laserdiscs and DVDs, and streaming could not even be imagined) and so movies could not be enjoyed on demand — unless you were content to replay just the audio of a movie you had recorded by placing a mic near the TV’s small speaker. I recorded many movies this way, listening to them repeatedly the way other people listened to their favorite records. Occasionally I listened to one tape so many times that I memorized it, and years later this questionable talent landed me the job of IMDb Quotes Editor.

Another of HBO’s main attractions from its earliest days was its “On Location” series, a collection of unexpurgated performances inaugurated in 1975 by the comedian Robert Klein (one of the top performers, with the likes of George Carlin, Richard Pryor, and Steve Martin, keeping the flame of standup comedy alive during the decade between its flowering in the 60’s and its explosive ubiquity in the 80’s). I was a fan, and in 1977, HBO aired a followup concert, “Robert Klein Revisited.” I tape-recorded it and there was just enough time before summer vacation for me to memorize big chunks of his routine.

School was out and we were among the annual migration of Jewish families from the swelter of New York City to a couple of months of bungalow-colony life in the Catskill mountains. Bungalow-colony life did not include TV. (And, in case contemporary readers need reminding, there was no Internet, nor any personal electronics.) For entertainment, we went outside.

Late one Friday afternoon, sitting at the picnic table in front of my bungalow, I “did” some of Robert Klein’s recent show for a couple of my friends. They laughed at the jokes, which felt tremendous, and even though it may have begun in conversational fashion, by the end I was in full-on performance mode. We all had a good time, even if some of the words coming out of my mouth went over all our heads.

The next Friday, one of my friends suggested I give a repeat performance, this time for a bigger audience. Without my really knowing what was happening, the word had spread about my “show” and there was now a group of a dozen or more kids in front of my bungalow. Rather than sit at our picnic table I stood atop it. I did exactly the same material in exactly the same way as the week before. And I killed! My mom, amazed, watched from the door of the bungalow as her very own Borscht Belt tummler worked the crowd, a story she told and retold for the rest of her life. (My dad would arrive later that evening, along with all the other dads after a week at work in the city.) Meanwhile, my original couple of friends, who’d heard exactly the same routine a week earlier, listened to my new fans’ cheers with pride at having been in on the act at the beginning.

One week later, my Friday-afternoon act had transformed into a ritual. Someone announced it over the P.A. system! The crowd in front of my bungalow had grown to 20-30 people, including a few bemused adults. My original couple of friends were now my handlers, prepping me for my performance. All of this had somehow happened without any involvement from me. For my part I was awhirl at being the center of attention, but was also growing reluctant to do the show. For one thing, I had no new material, and largely a returning audience who’d heard it all before. For another, I simply didn’t understand at least 10% of what I had memorized, and so I could do nothing other than repeat it as faithfully to the audience as my tape recorder had repeated it to me and hope that they responded just as faithfully with the laughter that the recording had led me to expect. I had no ability, none at all, to riff, edit, or otherwise adapt the material to the mood of the “room.” I could not have articulated that at the time, but thinking on your feet is of course an essential skill at the heart of standup comedy, and I was vaguely aware of, and uncomfortable about, not having it.

As expected, my recitation of Klein’s lines was received less enthusiastically than the week before, for the expected reasons. There was still laughter and applause, but none of that energy that flows like a current between audience and performer when things are going well. I was considerably less thrilled to be the center of attention. Still, it was enough of a success that when the following Friday rolled around, I was enjoined to perform yet again.

But I found very quickly that it was no longer about me or the act — if it ever even had been. The ritual was now about the ritual itself. A couple of friends, having armed themselves with water pistols, proclaimed themselves my bodyguards and insisted on escorting me during the preliminaries leading up to the show. This included a trip to the P.A. shack, where another self-appointed minion was in charge of announcing the upcoming show to one and all, and where my job apparently was to supervise the announcement. On the way back from there we encountered another group seeking to do crowd control or distribute fruit juice from my mom or perform some other show-related job, and my bodyguards got bossy and territorial. It was tribal, and it was ugly, and I didn’t like it. Before long, too many competing interests trying to impose too many different kinds of organization on an event too flimsy to bear much organizing in the first place caused the whole thing to fizzle. I did not go on, and the ritual did not repeat, and I was relieved. (Anyway, it was time for the summer to become all about Star Wars.)

To sum up: I had a message, and I delivered it to a growing and receptive audience. Yet my delivery of this message was the seed crystal around which an elaborate structure formed, a structure that had little or nothing to do with me or my message, and everything to do with the needs of the people forming it: their need for power, their need for meaning, their need to feel useful, their need to be part of something larger than themselves. Does this make you think of any major world religions, and the humble message-delivering central figure they all claim in common?

Again, can’t stress enough: not likening myself to Jesus. For one thing, his message actually was his. For another, I don’t doubt his riffing ability.

I’m grateful to Wired for publishing

I’m grateful to Wired for publishing  Well, guess what? Kill Ralphie! lives again! I’ve taken that old pastime and turned it into a fun new website. Please check it out, contribute chapters, and enjoy:

Well, guess what? Kill Ralphie! lives again! I’ve taken that old pastime and turned it into a fun new website. Please check it out, contribute chapters, and enjoy:

It was a line spoken by Michael O’Hare as Jeffrey Sinclair in Babylon 5. I have used that sentiment a few times since then as a way to gauge my readiness for something — starting a family, for instance. If I can’t say that line with conviction I know I’m kidding myself.

It was a line spoken by Michael O’Hare as Jeffrey Sinclair in Babylon 5. I have used that sentiment a few times since then as a way to gauge my readiness for something — starting a family, for instance. If I can’t say that line with conviction I know I’m kidding myself.