The latest Indiana Jones movie, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, came out in 1989 and was set in the year 1938. Next year, George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Harrison Ford will present a fourth Indiana Jones movie. In real time, 19 years will have elapsed since the last one.

Since Harrison Ford has visibly aged in that time, it’s reasonable to expect that a comparable interval has elapsed in story time between Indy 3 and Indy 4. Let’s say that the story interval is not 19 years but 24. That opens up a pretty interesting story possibility.

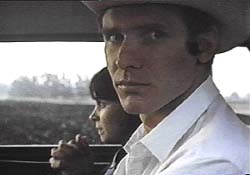

It’s 1962. An aging Indiana Jones has made a discovery of tremendous personal importance to himself, something he’s been looking for all over the world for thirty years. And for some reason, the first thing he does is to make his way to a small city in California to track down an obnoxious loudmouth with a fast car and a taste for Stetson cowboy hats — Bob Falfa.

Jones tries to convince Falfa to accompany him on a highly unique project. Mysteriously, Jones tells Falfa that he can divulge no details (“You wouldn’t believe me if I told you”) but, knowing Falfa’s love of fast cars, promises him the chance to drive something faster than anyone’s ever seen.

Jones tries to convince Falfa to accompany him on a highly unique project. Mysteriously, Jones tells Falfa that he can divulge no details (“You wouldn’t believe me if I told you”) but, knowing Falfa’s love of fast cars, promises him the chance to drive something faster than anyone’s ever seen.

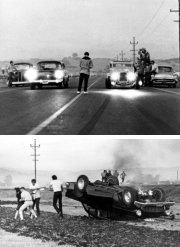

This was the wrong thing to say. Bob Falfa’s pride is hurt; his own car, he asserts, is the fastest thing on wheels. “And I’ll prove it to you!” Falfa storms off before Jones can get another word in and, almost at once, he goads a local hood, John Milner, into a drag race — which Falfa loses, spectacularly, trashing his car in the process.

This was the wrong thing to say. Bob Falfa’s pride is hurt; his own car, he asserts, is the fastest thing on wheels. “And I’ll prove it to you!” Falfa storms off before Jones can get another word in and, almost at once, he goads a local hood, John Milner, into a drag race — which Falfa loses, spectacularly, trashing his car in the process.

Humiliated, Falfa leaves town that very day and changes his identity, swearing off hot rods and Stetson hats in a bid to be untraceable. (But he can’t completely break with the past. His new name, Martin Stett, commemorates his preferred hatmaker.) Stett kicks around for a few years and ends up with a gig in San Francisco as the personal assistant to a wealthy and unsavory businessman known as The Director.

Late one night Stett finds himself in a high-stakes poker game with some hardcore gamblers, including one charming out-of-towner (“I’m just passing through”) who’s losing badly. Out of funds on a big hand, the stranger puts his pink slip in the pot, assuring everyone that it’s for “the fastest hunk of junk in the galaxy.” Stett wins the hand — and learns to his astonishment that he’s the new owner of a spaceship called the Millennium Falcon. The stranger, Lando Calrissian, is devastated but gracious in defeat. He offers to give piloting lessons to Stett in return for a lift back to his home galaxy far, far away.

Late one night Stett finds himself in a high-stakes poker game with some hardcore gamblers, including one charming out-of-towner (“I’m just passing through”) who’s losing badly. Out of funds on a big hand, the stranger puts his pink slip in the pot, assuring everyone that it’s for “the fastest hunk of junk in the galaxy.” Stett wins the hand — and learns to his astonishment that he’s the new owner of a spaceship called the Millennium Falcon. The stranger, Lando Calrissian, is devastated but gracious in defeat. He offers to give piloting lessons to Stett in return for a lift back to his home galaxy far, far away.

After dropping off Calrissian at a bustling spaceport, Stett flies around this new galaxy for several years, picking up odd jobs where he’s able and enjoying his new solitude so much that he changes his name again, this time to Solo. Over time he befriends a Wookiee, a Jedi, and a princess, and plays a role in reforming galactic politics.

Feeling nostalgic one day, Solo takes a long flight back to Earth and is a little puzzled to discover that, due to the time-distorting effects of faster-than-light travel, he has arrived years before he left. Thus unable to visit his old stomping grounds — they don’t exist yet! — he makes to leave immediately but the Falcon’s hyperdrive, which has always been finicky, gives out altogether. Solo is stranded on a planet where there are no spare hyperdrive parts for thousands of light years in every direction.

Feeling nostalgic one day, Solo takes a long flight back to Earth and is a little puzzled to discover that, due to the time-distorting effects of faster-than-light travel, he has arrived years before he left. Thus unable to visit his old stomping grounds — they don’t exist yet! — he makes to leave immediately but the Falcon’s hyperdrive, which has always been finicky, gives out altogether. Solo is stranded on a planet where there are no spare hyperdrive parts for thousands of light years in every direction.

With no other options, he conceals the Falcon in the New Mexico desert and begins researching ways to rebuild the hyperdrive from raw materials available on Earth. His research reveals the existence of ancient Etruscan mineral-smithing techniques that produced artifacts suitable for use in the hyperdrive motivator.

Solo begins hunting for Etruscan artifacts all over the world and is soon drawn into the world of archaeology, for which he has adopted yet another new alias — Indiana Jones — and reindulged his old love of broad-brimmed headwear. Along the way he has numerous new adventures and his repair of the still-concealed Millennium Falcon is sidetracked into an on-again, off-again project whose highlight is a dramatic near-crash during a test flight in 1947.

Solo begins hunting for Etruscan artifacts all over the world and is soon drawn into the world of archaeology, for which he has adopted yet another new alias — Indiana Jones — and reindulged his old love of broad-brimmed headwear. Along the way he has numerous new adventures and his repair of the still-concealed Millennium Falcon is sidetracked into an on-again, off-again project whose highlight is a dramatic near-crash during a test flight in 1947.

Finally, by 1962, Jones/Solo/Stett/Falfa has accumulated enough Etruscan jewelry and pottery and so on to build a hyperdrive motivator and complete the Falcon’s repair. However, he is by now old enough that his arthritis robs him of the agility needed to crawl in and among the parts of the Falcon’s engine machinery. What he needs is someone younger, mechanically inclined, and trustworthy. He knows just the person: an aimless young hot-rodder named Bob Falfa. And this time he won’t insult his car…

A little later, while we were watching another episode, Andrea came home. I asked her, “Can you guess whose voice that is doing the narration?”

A little later, while we were watching another episode, Andrea came home. I asked her, “Can you guess whose voice that is doing the narration?”

Jones tries to convince Falfa to accompany him on a highly unique project. Mysteriously, Jones tells Falfa that he can divulge no details (“You wouldn’t believe me if I told you”) but, knowing Falfa’s love of fast cars, promises him the chance to drive something faster than anyone’s ever seen.

Jones tries to convince Falfa to accompany him on a highly unique project. Mysteriously, Jones tells Falfa that he can divulge no details (“You wouldn’t believe me if I told you”) but, knowing Falfa’s love of fast cars, promises him the chance to drive something faster than anyone’s ever seen. This was the wrong thing to say. Bob Falfa’s pride is hurt; his own car, he asserts, is the fastest thing on wheels. “And I’ll prove it to you!” Falfa storms off before Jones can get another word in and, almost at once, he goads a local hood, John Milner, into a drag race — which Falfa loses, spectacularly, trashing his car in the process.

This was the wrong thing to say. Bob Falfa’s pride is hurt; his own car, he asserts, is the fastest thing on wheels. “And I’ll prove it to you!” Falfa storms off before Jones can get another word in and, almost at once, he goads a local hood, John Milner, into a drag race — which Falfa loses, spectacularly, trashing his car in the process. Late one night Stett finds himself in a high-stakes poker game with some hardcore gamblers, including one charming out-of-towner (“I’m just passing through”) who’s losing badly. Out of funds on a big hand, the stranger puts his pink slip in the pot, assuring everyone that it’s for “the fastest hunk of junk in the galaxy.” Stett wins the hand — and learns to his astonishment that he’s the new owner of a spaceship called the Millennium Falcon. The stranger, Lando Calrissian, is devastated but gracious in defeat. He offers to give piloting lessons to Stett in return for a lift back to his home galaxy far, far away.

Late one night Stett finds himself in a high-stakes poker game with some hardcore gamblers, including one charming out-of-towner (“I’m just passing through”) who’s losing badly. Out of funds on a big hand, the stranger puts his pink slip in the pot, assuring everyone that it’s for “the fastest hunk of junk in the galaxy.” Stett wins the hand — and learns to his astonishment that he’s the new owner of a spaceship called the Millennium Falcon. The stranger, Lando Calrissian, is devastated but gracious in defeat. He offers to give piloting lessons to Stett in return for a lift back to his home galaxy far, far away. Feeling nostalgic one day, Solo takes a long flight back to Earth and is a little puzzled to discover that, due to the time-distorting effects of faster-than-light travel, he has arrived years before he left. Thus unable to visit his old stomping grounds — they don’t exist yet! — he makes to leave immediately but the Falcon’s hyperdrive, which has always been finicky, gives out altogether. Solo is stranded on a planet where there are no spare hyperdrive parts for thousands of light years in every direction.

Feeling nostalgic one day, Solo takes a long flight back to Earth and is a little puzzled to discover that, due to the time-distorting effects of faster-than-light travel, he has arrived years before he left. Thus unable to visit his old stomping grounds — they don’t exist yet! — he makes to leave immediately but the Falcon’s hyperdrive, which has always been finicky, gives out altogether. Solo is stranded on a planet where there are no spare hyperdrive parts for thousands of light years in every direction. Solo begins hunting for Etruscan artifacts all over the world and is soon drawn into the world of archaeology, for which he has adopted yet another new alias — Indiana Jones — and reindulged his old love of broad-brimmed headwear. Along the way he has numerous new adventures and his repair of the still-concealed Millennium Falcon is sidetracked into an on-again, off-again project whose highlight is a dramatic near-crash during a test flight in 1947.

Solo begins hunting for Etruscan artifacts all over the world and is soon drawn into the world of archaeology, for which he has adopted yet another new alias — Indiana Jones — and reindulged his old love of broad-brimmed headwear. Along the way he has numerous new adventures and his repair of the still-concealed Millennium Falcon is sidetracked into an on-again, off-again project whose highlight is a dramatic near-crash during a test flight in 1947. Are there many or few such people?

Are there many or few such people?