We all live like kings of old

With running water, hot and cold

By armed defenders towns patrolled

When we command it, stories told

At night, soft beds do us enfold

No need to wear a crown of gold

Or prove oneself with exploits bold

We all now live like kings of old

Author: bobg

End of term report

Quantitatively, though, I get a C-minus. I only made it 72% of the way toward my goal. I’m 9.6% lighter than I was one year ago; I was aiming for 13.4%. (On the other hand, if you measure from my heaviest point, which was less than one year ago, to my lightest point, which was a few days ago, I lost 10.8% of my body weight.)

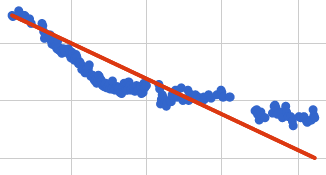

As you can see from the graph, after an exciting fast start, losing weight was a stop-and-go proposition.

At Google, teams are encouraged to set measurable goals at the beginning of each quarter, and then to measure them at the end of each quarter. Scores of 100% are great, of course, but we’re taught that the ideal average score is actually around 70%. More than that and your goals aren’t ambitious enough. So maybe I should feel satisfied with my 72% (but I don’t).

My bathroom scale also measures body composition. According to that scale, my body-fat percentage went from “very high” to merely “high,” and my visceral fat number went from “high” to “normal.” My muscle-to-fat ratio climbed from 1.02 to 1.38. Gratifyingly, my “body age,” according to the scale, dropped from 56 to my actual age: 47.

My goal for the coming year is to lose another 10.2% of my weight. If I’m successful, my body-fat percentage will drop from “high” to “normal.” I’d also like to see my scale claim that my “body age” is lower than my actual age. Wish me luck…

The Sigma Tax

Another thing that economists have long said is, “When you tax something, you get less of it.” So here’s an idea: let’s tax income disparity!

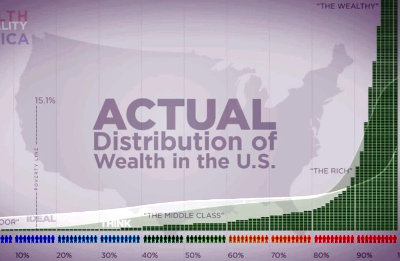

How would this work? Easy. For companies of a given size, we decide what the ideal distribution is of wages and other compensation. We might decide, for instance, that the 90th percentile should be earning no more than 50x what the 10th percentile earns. Whatever numbers we choose, the result is a curve; presumably a less-pronounced one than this:

Once we decide on the shape of our curve, companies are free to obey it or not, distributing their compensation however they see fit. But if their curves deviate too far from the ideal, they pay a proportional income-disparity tax. Maybe they can even be eligible for an income-disparity credit if the curves deviate in the other direction.

Properly tuned, and phased in slowly, this “Sigma Tax” (for the Greek letter that designates standard deviation in statistics) should result in gentle but inexorable pressure that reduces the wage gap, improving things for the bottom 99% without breaking the 1%, while paring some of their shameful excess.

Practice makes perfect

When I was young, a number of things came easily to me. In particular, I excelled in school and earned a lot of praise with very little effort. Nice as that was, there was a downside: I had little patience for things I wasn’t naturally good at, like sports or dancing or playing piano. Even though I longed to be able to play music, and even though I made a few sincere starts at trying to learn, when I perceived the gulf between my ability and where I wanted to be I gave it up.

Of course I’ve always understood intellectually that training is how people get good at things, but I was well into adulthood before the reality of that fact managed to sink in — just in time to have a job, a dog, a wife, a house, two kids, and no free time to myself for practicing things. Just think of all the things I could be good at today if I had believed at a young age that it was possible to be!

Happily my kids don’t have that handicap. They’ve seen for themselves — with piano, parkour, martial arts, soccer, fencing, and more (not to mention reading, writing, and arithmetic) — that real progress comes with practice. The secret to teaching this lesson was to recognize even slight interest by the kids in a variety of activities, and once recognized, to compel their participation in those activities until they were over the “I can’t do it” hump. After that, quitting for other reasons was OK, like genuine loss of interest, or prioritizing another activity. But again and again it happened that slight interest turned into strong interest once the “I can do it” confidence began to flow.

Glad had rad dad

When I was a kid

I had a great dad

He set an example

When I was mad, glad, or sad

Eventually

Two of my own kids I had

Now thanks to him

I’m not doing too bad

(Previously.)

Kids provoke the darnedest thoughts

A few days ago, as Archer and I were driving somewhere in the car, he asked me this question clear out of the blue: If you could live forever, what would you want to accomplish?

I have seldom heard a more profound question, and I told him so. After a moment’s thought, the answer that popped into my head — and from then until now, the only real answer that has occurred to me — was, “Help people use the Earth more responsibly.”

I do my part: I recycle, I drive a fuel-economical car, I vote in favor of open-space measures, I turn off lights, and so on. But that’s armchair environmentalism. Archer’s question, and my surprising reply, makes me think maybe it’s time to start doing more. I don’t expect to live forever, but I do hope my descendants will. Shouldn’t I act as if that’s the same thing?

Counting the bits at YouTube

Jonah is nearly done with fifth grade. In the fall he begins middle school. For years I’ve known that if I’m ever going to visit his classroom for a “what my dad does at work” presentation, it would have to be before middle school, which is when the coolness of “what my dad does at work” presentations falls off a cliff.

I made it just under the wire. For a long time all I had were good intentions and a half-started slide deck, work on which always took a backseat to this and that. Finally, a few weeks ago I gave his classroom the presentation below.

It was a hit. YouTube has a lot of cachet with 10-year-olds. It helped that I made some of the presentation interactive; there was a novelty factor to having the class work out some simple but enormous numbers. They stayed engaged for the full forty-five minutes, volunteering answers, laughing in the right places, and asking smart questions.

At the end I distributed light-up YouTube yo-yos to everyone, which was an even bigger hit. Hopefully it cemented Jonah’s reputation as the coolest kid to know. But his classmates were into the talk even before they knew there was swag coming.

I invite you to reuse or repurpose the slides below. I plan to give the talk again in two years when Archer is in fifth grade, so any constructive feedback that I can incorporate before then would be welcome.

The return of Mucoshave

The Brick Prison Playhouse

It’s the thirtieth anniversary of The Brick Prison Playhouse.

Alumni of Hunter College High School always seem compelled to mention that it’s where they attended the seventh through twelfth grades, when others would simply say “where I went to high school.”

It’s understandable. First there’s the confusing name of the place: it’s neither a college nor merely a high school. Second, when you’re in the habit of telling stories from high school, and some of them take place in 1978 and some take place in 1984, unless you’re diligent about the seventh-through-twelfth disclaimer sooner or later someone is going to do the mental arithmetic and wonder.

As a junior, late in 1982, a few friends and I felt the urge to write and perform a collection of short one-act plays. With faculty help we ended up founding The Brick Prison Playhouse (so called because the school’s appearance earned it the affectionate nickname “the brick prison”), a repertory group for performing student-written plays, as opposed to the existing repertory groups that performed established plays and musicals.

As a junior, late in 1982, a few friends and I felt the urge to write and perform a collection of short one-act plays. With faculty help we ended up founding The Brick Prison Playhouse (so called because the school’s appearance earned it the affectionate nickname “the brick prison”), a repertory group for performing student-written plays, as opposed to the existing repertory groups that performed established plays and musicals.

Our first performances took place on February 10th and 11th, 1983. They were a success and a lot of fun. After the last performance the entire playhouse group trekked through Central Park in a light snowfall to the Upper West Side apartment of our friend Michael, where we had a memorable cast party — and ended up snowed in. The only reason I know the exact dates is because it was the great New York Blizzard of 1983.

The next morning, I had to make it back to Queens, but transit had been only partially restored throughout the city. Exiting Michael’s building I was amazed to discover that Broadway was navigable only via a shoulder-high snow trench, just wide enough for two pedestrians to squeeze past each other. Through this narrow channel I worked my way downtown to where working buses and subways could be found — with my also-Queens-bound friend Steve in tow, on crutches with a broken ankle!

(Steve was the best writer in our group. The most talented actor among us was Andrew. I’m pleased to report that today Steve is a professional writer and Andrew a professional actor.)

On the radio program Fresh Air the other day, I heard an interview with the journalist Chris Hayes. In it, he mentions that he grew up in New York City, attended a school from the seventh through the twelfth grades, and performed in a student-written play in the eighth grade. From this I concluded (correctly) that Hayes is a Hunter alumnus, and that The Brick Prison Playhouse still exists!

It occurs to me this is the second blog post in a row where I lay claim to an unacknowledged legacy. Well, acknowledged or not, this one’s an agreeable legacy to have, and the Brick Prison Playhouse’s near-mention on Terry Gross’s widely heard radio show is a nice little brush with fame on this, its thirtieth anniversary.

Coffee optimization

Doctoring the coffee after brewing added a good twenty or thirty seconds to the total coffee preparation time, a substantial increase over the time needed by the machine. But the machine’s user waits idly for seventy-four seconds; why not put that time to better use?

When I started at YouTube a few years ago I encountered fancy coffee machines in the break rooms (or in Google parlance, “minikitchens”). At the touch of a button it would dispense a single serving’s worth of coffee beans from a hopper into its internal grinder, grind them up, add water from a supply line, and brew and serve a cup of hot coffee, all in seventy-four seconds. (I timed it.)

Occasionally a line would form of coffee addicts needing their fix. Most had the same routine: when one brew cycle was finished, the next person in line would place his or her cup in the machine and press the button. Seventy-four seconds later they’d withdraw their cup, add sugar, carry it over to the cooler, take out the half-and-half, and add that; then leave.

Doctoring the coffee after brewing added a good twenty or thirty seconds to the total coffee preparation time, a substantial increase over the time needed by the machine per se. But the machine’s user waits idly for seventy-four seconds; why not put that time to better use? After several months it dawned on me to change my routine. As soon as the previous user’s cycle ended, I pressed the start button without putting a cup in the machine. Instead, during the first thirty or so seconds of grind-and-brew time, I put sugar and half-and-half into my empty coffee cup, then placed it in the machine. By the time the machine was finished, I was all ready to go, about 25% faster than everyone else.

In hindsight it was an obvious optimization to make, and in an office full of bright, busy engineers I was surprised that I was the only one I had ever observed making it. I did occasionally get some appreciative glances from others on seeing my technique in action, and finally within the past year I’ve noticed my method catching on. It’s gratifying to be a trendsetter, but frustrating to be unacknowledged. At least I can tell you about it.