- A boy and his dog, part 1: Pittsburgh to Bloomington

- A boy and his dog, part 2: Bloomington to Davenport

- A boy and his dog, part 3: Davenport to Omaha

- A boy and his dog, part 4: Omaha to Rawlins

- A boy and his dog, part 5: Rawlins to Salt Lake City

- A boy and his dog, part 6: Salt Lake City to Winnemucca

- A boy and his dog, part 7: Winnemucca to San Rafael

(Continued from yesterday.)

I began the morning of April 9th, 1992, in pretty bad shape. I had barely slept. Although Alex had endured no fewer than four changes of address with me and Andrea without complaint in her short time on Earth, this had been her first night in a motel. She had jerked awake at every unfamiliar sound — so, so did I, knowing after the first two or three instances that, without my soothing intervention (or even occasionally with it), a barking fit was likely to follow. I fully expected to be asked to leave the motel in the middle of the night. Instead I merely had an extremely hard night.

I showered and dressed, walked Alex, loaded her and my things back into my car, checked out of the motel, and finally met Tall Steve. We spent an enjoyable morning together during which he showed off the offices of The Bloomington Voice, a free alternative weekly that he founded and edited where he was the founding art director/production manager (correction from Tall Steve — but he has founded or owned other Bloomington institutions). The Voice, which achieved significant local renown, was a natural outgrowth of his numerous extracurricular deeds at CMU and was only the beginning of his deep involvement in Bloomington civic life. (That, too, was prefigured by his activities in Pittsburgh, where he was constitutionally incapable of remaining uninvolved with improving student society — which may be what lent such weight to his “Accomplish something, dammit” admonition.)

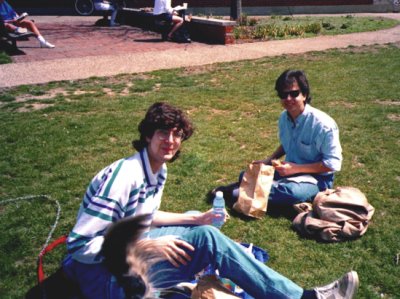

We concluded our morning together with a picnic lunch on the Indiana University campus (the site of two things — coincidentally both from 1979 — that changed my life: the movie Breaking Away and Douglas Hofstadter’s book Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid). I’d tethered Alex nearby with a special corkscrew-shaped dog stake attached to her leash. But in her excitement she pulled it clean out of the ground and began to bolt across the lawn, pointy-corkscrew-stake bouncing along dangerously behind her. (In those days she was much less well-behaved than she eventually became.) I had to simultaneously eat, hold Alex, and keep her away from our food.

Soon afterward, Alex and I were back on the road, headed for our next stop: Davenport, Iowa (Captain Kirk’s home state!), just across the mighty Mississippi River, where we would join Interstate 80 and ride it the entire rest of the way to California.

In 1954, at age 18, my dad and his friend undertook an epic almost-penniless hitchhiking journey from New York to California. I had grown up on his stories from that adventure, not to mention countless road-trip movies, TV shows (reruns of Route 66 were required viewing in college), songs, and the granddaddy of the genre, Kerouac’s On the Road (the famous original scroll of which, in another weird coincidence, was recently housed for a while at… Indiana University). They glamorized the idea of hitting the open road and traveling this great country, the better to “find yourself” — sort of an American version of walkabout.

In 1954, at age 18, my dad and his friend undertook an epic almost-penniless hitchhiking journey from New York to California. I had grown up on his stories from that adventure, not to mention countless road-trip movies, TV shows (reruns of Route 66 were required viewing in college), songs, and the granddaddy of the genre, Kerouac’s On the Road (the famous original scroll of which, in another weird coincidence, was recently housed for a while at… Indiana University). They glamorized the idea of hitting the open road and traveling this great country, the better to “find yourself” — sort of an American version of walkabout.

On this score my trip was shaping up to be pretty disappointing. We drove straight to Davenport. On the bridge into town I glanced down at the Mississippi. It wasn’t so mighty. We checked into the motel, watched some TV, and went to sleep. Not only did the interstate isolate me from all possible interactions with gorgeous co-stars in each town I passed through like Tod and Buz, but having Alex along cramped my style even further.

Only now do I understand that the “open road” in those works, with its twists and turns, sometimes giving you choices, sometimes taking you you-know-not-where, bringing you into contact with as many different people, places, and situations as your own intrepidity will allow, is a metaphor for life itself, and I’ve been on it all along. At long last I’ve finally begun to find myself.

(…to be continued…)