Before the iPhone and the Blackberry was the Sidekick, a.k.a. the Hiptop, the first mass-market smartphone and, for a while, the coolest gadget you could hope to get. Famously, and awesomely, the Hiptop’s spring-loaded screen swiveled open like a switchblade at the flick of a finger to reveal a thumb-typing keyboard underneath, one on which the industry still hasn’t managed to improve. Your Hiptop data was stored “in the cloud” before that term was even coined. If your Hiptop ever got lost or stolen or damaged, you’d just go to your friendly cell phone store, buy (or otherwise obtain) a new one, and presto, there’d be all your e-mail, your address book, your photos, your notes, and your list of AIM contacts.

The Hiptop and its cloud-like service were designed by Danger, the company I joined late in 2002 just as the very first Hiptop went on the market. I worked on the e-mail part of the back-end service, and eventually came to “own” it. It was a surprisingly complex software system and, like much of the Danger Service, required continual attention simply to keep up with rising demand as Danger’s success grew and more and more Sidekicks came online.

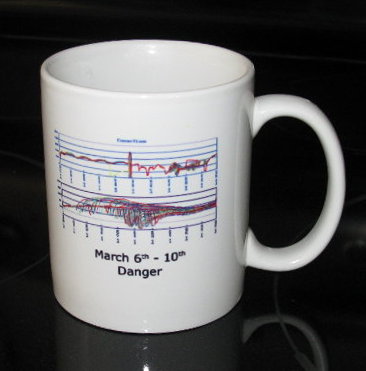

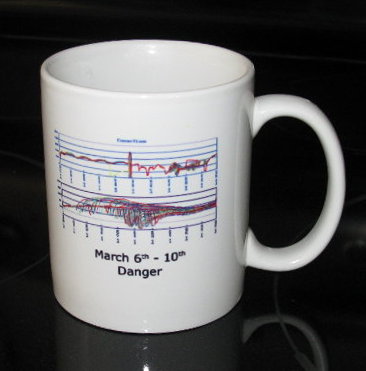

Early in 2005, the Danger Service fell behind in that arms race. Each phone sought to maintain a constant connection to the back end (the better to receive timely e-mail and IM notices), and one day we dropped a bunch of connections. I forget the reason why; possibly something banal like a garden-variety mistake during a routine software upgrade. The affected phones naturally tried reconnecting to the service almost immediately. But establishing a new connection placed a momentary extra load on the service as e-mail backlogs, etc., were synchronized between the device and the cloud, and unbeknownst to anyone, we had crossed the threshold where the service could tolerate the simultaneous reconnection of many phones at once. The wave of reconnections overloaded the back end and more connections got dropped, which created a new, bigger reconnection wave and a worse overload, and so on and so on. The problem snowballed until effectively all Hiptop users were dead in the water. It was four full days before we were able to complete a painstaking analysis of exactly where the bottlenecks were and use that knowledge to coax the phones back online. It was the great Danger outage of 2005 and veterans of it got commemorative coffee mugs.

The graphs depict the normally docile fluctuations of the Danger Service becoming chaotic

The outage was a near-death experience for Danger, but the application of heroism and expertise (if I say so myself, having played my own small part) saved it, prolonging Danger’s life long enough to reach the cherished milestone of all startups: a liquidity event, this one in the form of purchase by Microsoft for half a billion in cash, whereupon I promptly quit (for reasons I’ve discussed at by-now-tiresome length).

Was that ever the right move. More than a week ago, another big Sidekick outage began, and even the separation of twenty-odd miles and 18 months couldn’t stop me feeling pangs of sympathy for the frantic exertions I knew were underway at the remnants of my old company. As the outage drew out day after day after day I shook my head in sad amazement. Danger’s new owners had clearly been neglecting the scalability issues we’d known and warned about for years. Today the stunning news broke that they don’t expect to be able to restore their users’ data, ever.

It is safe to say that Danger is dead. The cutting-edge startup, once synonymous with must-have technology and B-list celebrities, working for whom I once described as making me feel “like a rock star,” will now forever be known as the hapless perpetrator of a monumental fuck-up.

It’s too bad that this event is likely to mar the reputation of cloud computing in general, since I’m fairly confident the breathtaking thoroughness of this failure is due to idiosyncratic details in Danger’s service design that do not apply at a company like, say, Google — in whose cloud my new phone’s data seems perfectly secure. Meanwhile, in the next room, my poor wife sits with her old Sidekick, clicking through her address book entries one by one, transcribing by hand the names and numbers on the tiny screen onto page after page of notebook paper.